Today, the Lafayette Commemorative Silver Dollar remembers when Congress voted on February 4, 1824, to send a war ship to bring the general to the United States for a visit.

From Lafayette’s Visit to Germantown, by Charles Francis Jenkins, published in 1911:

=====

In the same session of Congress which had been opened by that message from the President conveying to it, and to the world, the so-called Monroe Doctrine, there was passed, February 4, 1824, a resolution offering to the Marquis de Lafayette a ship of war to bring him to America to pay the visit he had long planned, and which this nation was then eagerly anticipating.

Leaving his country home, La Grange, an estate of some eight hundred acres lying forty miles east of Paris, which through many vicissitudes had been his refuge, he set out on what was to be one of the most remarkable visits in the annals of the world, an event which Charles Sumner declared was one of the poems of history.

And if this episode belongs to the poetry of history, the whole life and career of Lafayette constitute one of its most striking romances.

Born of illustrious parents, a posthumous son, the death of his mother left him an orphan at an early age. Soon after the boyhood heir of a large fortune, married before he was seventeen to a young woman of one of the leading noble families of France, a father at eighteen, he became fired with zeal for the American cause at nineteen, on listening to a recital of the Colonies’ wrongs by one of the last persons you would expect—the Duke of Gloucester— brother of the English king.

Shortly after this meeting, Lafayette visited his uncle, the French Ambassador in London, and was presented to George the Third himself. He had already offered his services to the American Commissioners in Paris, and on his return to France he hid himself from his wife and family, the latter being bitterly opposed to his course.

Without a parting farewell to those he loved, he stole away from Paris, eluded the agents of the government, and after many vexatious delays sailed from a Spanish port for America in company with Baron de Kalb.

He presented himself, not yet twenty years of age, with the commission of a Major-general in the American army, given him by Franklin and Deane, to the astonished Continental Congress, then sitting in Philadelphia.

Such is the brief record of Lafayette’s entry upon the American horizon, and romantic as it is, it is but a fitting prelude to nearly threescore more years, equally fraught with experiences and adventures such as have come to but few men.

Soon established in intimate daily companionship with Washington, he became through his military skill a Major-general in reality.

Wounded at Brandywine, nursed to health at Bethlehem, sharing the discomforts of Valley Forge, a successful tactician at Barren Hill and at Monmouth, given an independent command in Rhode Island, he everywhere met the confidence reposed in his ability and good judgment.

Sailing for France early in 1779, in the new frigate Alliance, he assisted in securing the substantial French reinforcements under Rochambeau.

Returning to America in the spring of 1780, he was later given command in the notable Virginia campaign, which ended with the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

The activities of the armies over, he returned to France, again sailing in the Alliance, and assisted the American Commissioners in the tortuous steps which led to the treaty of peace.

In 1784, he came to America on his third visit, was for a time the guest of Washington, his mentor and friend, at Mt. Vernon, and the recipient of many honors and attentions from the American people.

In the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, and the other great events which stirred Europe for four decades, he bore a conspicuous part, and was one of the very few—an able historian has said, “perhaps the only, Revolutionary leader of France whose record left nothing to blush for.”

His exile from his native land, his political imprisonment by the Austrians, shared in part by his devoted wife and daughters, in the noisome dungeons of Olmütz, the loss of his fortune,—all these were well known to his sympathetic American friends.

They had seen him standing as a bulwark of political liberty and human rights as exemplified in the cause of American Independence, and the forty years of separation, during which his star had risen and sunk repeatedly, but increased the esteem and affection which they bore him, and intensified their desire to welcome him.

Lafayette declined the offer of President Monroe and of Congress for passage in a public ship, and set sail in a merchant packet, the Cadmus, from Havre, July 13, 1824, and, after a pleasant voyage of thirty-two days, reached the harbor of New York on Sunday, the 15th of August.

The official landing was made on August 16th at the Battery. Here began a tour without parallel in our history. It lasted in all some fourteen months.

“The Nation’s Guest,” as he was called, traversed every state and section of the country.

From New York he proceeded through Connecticut to Boston, thence to Portsmouth, N. H. Returning to New York, he steamed up the Hudson to Albany.

Retracing his steps, he passed through New Jersey to Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, where he was received by Congress with great distinction and given $200,000 in money and a township of land in recognition of his Revolutionary service.

An extensive tour in Virginia and then on to Raleigh, Charleston, Savannah, Mobile and New Orleans.

By this time it was April, 1825, when he ascended the Mississippi to St. Louis; thence to Nashville, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, along Lake Erie to Niagara Falls; to Syracuse, Albany, Boston, and as far east as Portland, Me.

He returned to New York in time for the great celebration of July 4, 1825. Then to Philadelphia and again to Washington.

Everywhere there were receptions, dinners, balls, arches, school children drawn up along the roads, while frequently whole communities waited from dawn to sunset for the belated guest.

There were presentations, parades, salutes and speeches, over and over.

It seemed impossible for the various communities to give expression to their affection and overflowing good will; and the most wonderful part of it is that an elderly gentleman who celebrated his sixty-seventh and sixty-eighth birthdays during the tour could stand the terrific strain.

But Lafayette’s health, buoyed by his unfailing courtesy and good-nature, and his apparently sincere enjoyment of the attentions shown him, actually improved as the journey progressed, and the whole trip was accomplished without greater disaster than the wrecking of his steam boat on the Mississippi River through running on a snag, and from this accident the party was rescued from the sinking boat without much difficulty.

It should be recalled that Lafayette was the sole survivor of Washington’s generals.

At almost every centre some soldier of the Revolution would present himself, or be pushed forward by his friends, as a companion in arms.

Many of them had served under Lafayette in his favorite light infantry;—here the pilot who had brought him into port, or the officer to whom he had given a sword, or the companion of the cold and suffering of Valley Forge, would be recognized by Lafayette and as often called by name.

He was indeed a link joining the America of 3,000,000 souls of the struggling Colonies to the Union of twenty-four states and 10,000,000 prosperous people.

Everywhere he went the leading men of the country sought him out and welcomed him.

In Boston, on his second visit, Daniel Webster, the orator of the laying of the corner-stone of the Bunker Hill Monument on the 50th Anniversary of the Battle, addressed him with all the warmth of his affectionate rhetoric.

In the halls of Congress Henry Clay, speaker of the House, conveyed the nation’s respect and admiration.

In New England he met and renewed his early friendship with the venerable ex-President, John Adams; and at Monticello he did what has fallen to the lot of but few men—dined with three ex-Presidents, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe.

James Monroe, as President, welcomed him in the White House, and again President John Quincy Adams received him there on the return from his tour.

In 1824, Lafayette presented a fine portly figure, nearly six feet high, his sixty-seven years lightly worn, his only apparent infirmity being a slight limp, popularly attributed to his wound at Brandywine, but in reality caused by a broken hip, the result of a fall on the ice in 1803.

His face is said to have been without a wrinkle, and he wore a dark-red wig, set low on his forehead, which stood in good stead to one who was constantly bowing with uncovered head.

It is related that the Seneca chief, Red Jacket, who had met and known Lafayette in the early days, frankly expressed his amazement that the passing years should have left the General such a fresh countenance and a hairy scalp.

Lafayette was accompanied in his triumphal tour by his only son, George Washington Lafayette, then a mature man of forty-five, himself not without distinction, and later a senator of France. The third member of the party was Auguste Lévasseur, the secretary and historian of the trip. They were accompanied by One Servant.

=====

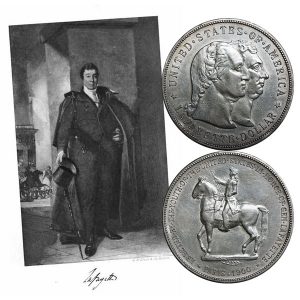

The Lafayette Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an image of a full-length portrait of the general, circa mid 1820s.