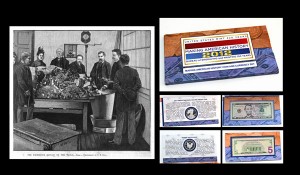

Today, the 150th Anniversary Coin and Currency Set from 2012 remembers the beginning of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on August 29, 1862.

The Harper’s Weekly of February 15, 1890 provided a detailed description of “How Uncle Sam Makes His Paper Money” by Franklin P. Smith.

Mr. Smith gave detailed information and the magazine included artists’ images of the different processes in place at that time.

The article began:

=====

The handsome building of brick and iron on the corner of Fourteenth and B streets, in the city of Washington, known as the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, owes its origin to the civil war.

Although it was not built until many years after that struggle, the work now going on under its roof was forced upon the government in the autumn of 1862.

Previous to this date the issues of paper-money were engraved and printed by private bank-note companies in New York city.

They were shipped to Washington in sheets of four notes each.

After being signed by the Treasurer of the United States and the Register of the Treasury, they were trimmed and cut up, or separated, by women with long sharp shears.

So slow, laborious, and expensive was the work, that Secretary Chase gave orders that it should be done by machinery.

On the 29th of August, 1862, Mr. Spencer. M. Clark, then Chief Clerk of the Bureau of Construction, to whom he entrusted the execution of these orders, had procured and set up in the basement of the Treasury the presses for printing the engraved signatures of the Treasurer and Register, and the trimmers and separators for making the notes ready for circulation.

From this humble beginning has expanded one of the most interesting and important branches of the Federal government.

Under Mr. Clark’s energetic and efficient management the bureau was a success from the first.

Overcoming the great opposition that he encountered from the private bank-note companies, he constantly enlarged the operations of the establishment.

It was but a step from printing the signatures on the notes to printing the notes themselves.

The further step of engraving the plates in the Treasury, instead of entrusting the work to private enterprise, was easily and naturally taken.

In a few months the government owned a completely equipped engraving and printing establishment, having its own engravers and printers, and its own stock of dies, rolls, and plates for the production of every form of security.

Although the bureau never failed to justify its existence by turning out work much cheaper than the bank-note companies, the policy of sharing with them the preparation of the paper issues prevailed for many years.

Greater security was believed to come from having the bank-note companies engrave and print the backs, while the bureau engraved the faces.

Whether justified or not by experience, the policy was finally abandoned.

To such a volume did the work of the bureau grow that the quarters in the attic of the Treasury, whither it was transferred from the basement, became entirely inadequate.

During the administration of Mr. Clark he proposed that a separate building, to be connected with the Treasury by a subterranean passage, be erected on the ground opposite the Albaugh Opera-house.

It was not, however, until the administration of Mr. Edward McPherson that Congress was induced to make an appropriation for the purpose.

With $27,000 for a site, and $300,000 for a building, construction was begun in the autumn of 1878, and completed in the spring of 1880.

The bureau was immediately removed to its new quarters, where it now gives employment to more than a thousand people.

At the time that Mr. Clark began operations he had only one male and four female assistants.

He remained Chief of the Bureau until August 16, 1868.

Since then the administration of the institution has been in the hands of George B. McCurtee (February 21, 1868, to February 17, 1876); Henry C. Jewell (February 21, 1876, to April 30, 1876); Edward B. McPherson (May 1, 1811 to September 30, 1878); 0. H. Irish (October 1. 1878, to January 27, 1883); Truman N. Burrill (March 30, 1883, to May 21, 1885); Edward 0. Graves (May 21, 1885, to May 1, 1889); and William M. Meredith, appointed to succeed him.

…

The other processes carried on in the bureau are in no way connected with the protection of securities against the skill and rascality of the counterfeiter; their object is simply the convenience of the public.

In order that the strip stamps on cigars and cigarettes, for example, may be the more easily detached, the sheets are perforated; revenue stamps of larger denominations, as well as checks, drafts, and warrants, are made more portable by being bound into books.

Certain kinds of work, like pension checks, are both perforated and bound, while other kinds, like cigarette stamps and fee stamps for the New York Custom-house, are gummed.

All these processes belong to the binding and perforating division, which also trims and separates such work as requires it, and all, except the binding, are facilitated by the use of machinery.

The protection of securities against loss or theft is constantly present in the minds of the officers of the bureau.

They omit no count and no lock to insure perfect safety, and so successful have they been that during the administration of Mr. Graves not the smallest loss occurred.

In the printing division, therefore, vaults form, as in the engraving division, an indispensable adjunct.

Every incomplete sheet, like every incomplete die or plate, is placed in them at night.

Checks and stamps of small value are deposited in the locker-like safes along the sides of the hall on the second floor, and in the basement near the binding and perforating division.

The more valuable work, like notes and bonds, is deposited in the large vault near the examining division.

As I have already said, all completed work goes to the vault division for delivery to the Treasury.

Had the bureau been built in accordance with Mr. Clark’s plan, the transportation of securities to the Treasury would not have been the stately and interesting affair that it now is.

Many visitors going to the bureau have doubtless observed rolling out of the yard, behind a spanking team of horses, a large covered wagon resembling a moving van, and wondered what it could possibly be.

Inquiry always brings out the fact that it is “the security wagon”; that it carries the printed securities from the bureau to the Treasury; that it is plated with iron to make it fire-proof; that it is surmounted by a guard to protect it against the assaults of any highwaymen that may be bold enough to attack it on the streets of Washington.

In it also is carried to the bureau the blank paper stored in the sub-basement of the Treasury.

In it, too, is brought back to the bureau the worn and mutilated currency that has been returned for redemption; for all the notes printed in the bureau that are not lost in circulation come back in from two to four years to be destroyed under official supervision.

Ignoble as the last end of these pieces of paper is, visitors to the bureau are always eager to see it.

Like them, I was unable to resist the temptation to witness the solemn ceremony.

In company with ten or fifteen ladies and gentlemen, I went one morning about half past eleven o’clock to a room in the rear of the laundry.

The Destruction Committee of the Treasury, with their old and decrepit, treasures, had not yet arrived.

We had therefore twenty minutes or more to look about.

Through two large round holes in the floor we saw two great cylinders of the size of locomotive boilers, called macerators.

Into these cylinders the worn-out notes, imperfectly printed securities, etc., are poured, by means of funnels inserted in the holes through which we were looking.

After they are mixed with lime and soda-ash, caps are placed over the ventricles, and fastened with a separate lock and key by each of the three members of the Destruction Committee, the steam is turned on, and the cylinders set in motion.

When the notes are thoroughly macerated, the mixture is drawn off into a stone trench under the cylinders, pumped up to a paper machine on the floor where we were, and manufactured into thick sheets of paper, which are made up in packages, and sold to paper-makers.

Some of the pulp of notes is cast into images and other forms, and sold in the fancy stores in Washington to the relic hunter.

The fabulous figures marked on them to indicate the face value of the notes in them seldom fail to stimulate his imagination and inflame his desire for possession.

In the meantime several boxes, securely fastened, have arrived; later followed the Destruction Committee.

A large funnel is inserted in one of the holes in the floor, and on a table drawn near it are emptied the contents of the boxes.

The spectators crowd around, and watch every movement of the committee.

With rude and inconsiderate haste the members cut the packages of notes, and push them into the mouth of the funnel.

When it becomes clogged, one of them seizes a long stick and clears away the obstruction. Finally the last packages are reached, ripped open, and thrown after their fellows.

As I turned away with a feeling of melancholy I saw a pretty woman, clinging to the arm of the gentleman at her side, look up into his face, and exclaim, in a low voice, “Oh, Harry, doesn’t that seem too bad!”

And I could not help thinking that it was the ignoble end of those old and most faithful of friends that millions of men and women struggle for from morning till night, that they fight for, that they die for — that it was the thought of the tales of battle and intrigue, of toil and crime that each might tell if given a voice, that brought the glistening dew to her soft brown eyes.

=====

The 150th Anniversary Coin and Currency Set shows with one of the artists’ images illustrating the destruction of old or damaged goods.