Today, the Kentucky State Quarter Coin remembers when Captain Harry Gordon, an engineer, camped near the Great Lick or Bone Lick on July 16, 1766.

Early explorers found many large animal bones in this area as early as 1729.

From The New Régime, 1765-1767 by Clarence Walworth Alvord, published in 1916, an excerpt of Captain Gordon’s journal:

=====

We remained near the Scioto until the 8th July. Observed and found the Lat 38° 09′.

The greatest Part of the Shawnee Nation were assembled here at the Desire of Mr. Croghan. This Nation is composed of a few, but choice men. Their influence over the Ouabache Indians is great, which joined to their situation and other circumstance, make them an object worthy our Attention.

Matters being settled with them, (although with difficulty) we pursued our route the 8th July.

The 16th we encamped opposite the Great Lick and next day I went with a party of Indians and Battoemen to view this much talked of place.

The beaten Roads from all quarters to it easily conducted us, they resemble those to an inland village where cattle go to and fro a large common.

The pasturage near it seems of the finest kind, mixed with grass and herbage, and well watered.

On our arrival at the Lick, which is 5 Miles distance S. of the River, we discovered laying about many large bones, some of which the exact patterns of elephants’ tusks, and others of different parts of a large animal.

The extent of the muddy part of the Lick is 3/4th of an acre. This mud being of a salt quality is greedily licked by buffalo, elk and deer who come from distant parts, in great numbers, for this purpose.

We picked up several of the bones some out of the mud, others off the firm ground, and returned; proceeded next day and arrived at the falls 19th July.

=====

In Appendix B of the First Explorations of Kentucky compiled by Josiah Stoddard Johnston, published in 1898, more information about Bone Lick area:

=====

Big Bone Lick, a series of salt springs, the most notable in Kentucky, is situated in the northern part of what is now Boone County, three or four miles south of the Ohio River.

Instead of being fifteen miles above the Falls at Louisville, as represented to Gist and as put down on the map of Lewis Evans and others, it is ninety-four miles above Louisville.

Gist does not claim to have been there, but some of his commentators have insisted that he was, and the maps have been contorted to conform to their theories.

It is famous as being the spot where was first found in America the bones of the Mastodon (Mastodon giganteus).

This prehistoric quadruped is described zoologically as “a new mammal resembling the elephant but larger and having tuberculate teeth, whence its name. The remains of the mastodon are found in the temperate parts of both hemispheres.”

As the locality ranks as a natural curiosity with the Mammoth Cave, peculiarly a Kentucky phenomenon but cursorily described or explained in our history, I deem it not inappropriate to insert here such matter respecting it as I have been able to collate.

I pretermit the question of the geologic age to which the animal belongs or the period at which the bones here found were entombed, while I incline strongly to the belief that it was synchronous with the age of man.

When or by what white man these bones were first found is not known, their first notation being upon the map of Charlevoix, 1744, who gives 1729 as the date of their discovery.

They were noticed in the journals of the subsequent explorers, and have for a century and more been an object of investigation and comment by the leading scientists of the world.

Captain M. F. Bossu, a French officer stationed at Fort Chartres in Illinois, makes the following reference to them in a letter dated there November 10, 1756:

“Yesterday an express arrived here from Fort DuQuesne to our Commander, who informs me that the English made great preparations to come to attack that place again. M. de Macarty has sent provisions to victual the fort. The Chevalier Villiers commands it in my stead, my bad health not permitting me to undertake that voyage. It would have enabled me to examine the place on the road where an Indian found some Elephant’s teeth, of which he gave me a grinder weighing about six pounds and a half. In 1735 the Canadians who came to make war upon the Tchicachas found near the fine river Ohio the skeletons of some Elephants, which makes me believe that Louisiana joins to Asia, and that their Elephants came from the latter continent by the western part, which we are not acquainted with. A herd of these Elephants having lost their way probably entered the new continent, and having always gone on main land and in forests, the Indians not having the use of fire arms were not able to destroy them entirely. It is possible that some arrived at the place on the Ohio which on our maps is marked with a cross. The Elephants were in a swampy ground, when they sunk in by the enormous weight of their bodies, and could not get out again, but were forced to stay there.”

George Croghan, in his journal of his trip down the Ohio in 1765, makes the following entry of May 30th:

“We passed the Great Miami River thirty miles from the little river of that name, and in the evening arrived at the place where the Elephants’ bones are found, where we encamped, intending to take a view of the place next morning, 31st. Early in the morning we went to the Great Lick where these bones are only found, about four miles from the river. In our way we passed through a fine timbered clear wood. We came into a large road which the buffaloes have beaten spacious enough for a wagon to go abreast, and leading straight into the Lick. It appears that there are vast quantities of these bones lying five or six feet underground, which we discovered in the bank at the edge of the Lick. We found here two about six feet long. We carried one with some other bones to our boat, and set off.”

Mann Butler’s History of Kentucky, Appendix, second edition, Cincinnati, 1836.

Captain Harry Gordon, in his Journal Appendix to Pownall’s Description, &c, London, 1776, who also visited the Lick, July 16, 1766, says he encamped opposite Big Bone Lick, about thirty miles southwest of the mouth of the Licking, called by him Great Salt Lick. “The extent of the muddy part of the Lick,” he says, “is three fourths of an acre.”

Captain Thomas Hutchins, heretofore referred to in these notes as being with him, says in his book, London, 1778, that the celebrated Doctor Hunter thought the bones of the mastodon were those of some carnivorous animal larger than an elephant.

In 1773 Captain Thomas Bullitt, Hancock Taylor, and James Douglas, surveyors, and others in their company, James McAfee, George McAfee, Robert McAfee, James McCoun, junior, and Samuel Adams, in another company descending the Ohio from the mouth of the Kanawha, where they had met by chance, stopped here and visited the Lick on the 4th and 5th of July. They found bones in great quantities, and made seats of the vertebra and tent poles of the ribs.

…

=====

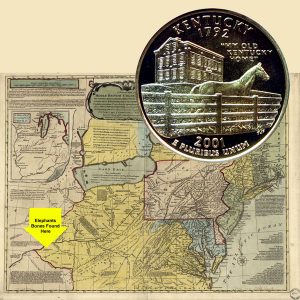

The Kentucky State Quarter Coin shows with a map of the Kentucky area, circa 1771, that includes “Elephants Bones found here.”