Today, the First Flight Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers the honors bestowed upon Col. Charles A. Lindbergh on June 13, 1927 and his flight from Washington, D.C.

From the Washington, D.C., Evening Star newspaper of June 13, 1927:

=====

Crash Feared as He Races Sharply Up Into Air.

Flying an Army Curtiss pursuit plane, tendered him after the Spirit of St. Louis was unable to take the air owing to engine trouble, Col. Charles A. Lindbergh took off from Bolling Field at 8:43 o’clock this morning with a gesture that struck terror into the hearts of airmen.

Once more the enthusiastic spectators recalled the name and fame of “Lucky” Lindbergh as they saw him race down the field in the speedy single-seater, pull it almost straight up into the air and climb almost vertically for three or four hundred feet. Had the engine failed nothing would have saved Col. Lindbergh from instant death.

When Col. Lindbergh left he made no plans for disposition of his plane other than to say he would let the naval air station know what to do with it when he got to New York. It was felt here that he would fly back to Washington in his Army pursuit plane, climb aboard the New York-Paris non-stop monoplane and continue his flight to St. Louis. Aviators believed that Col. Lindbergh would not want anyone else to fly the plane.

Guest of Airmen.

The dramatic departure from Washington came after 800 “air people” of Washington tendered the noted airman a breakfast at the Mayflower Hotel while some 200 looked on from the balconies. In a brief address, Col. Lindbergh admonished airmen aspiring to make the Pacific flight not to use the type of navigation that he did, but to rely on radio and celestial navigation. He predicted oceanic air travel, but declared it would have to be backed by a sound business organization on the ground.

At this function he was awarded the highest honors of the National Geographic Society and the National Aeronautic Association, under the auspices of which latter organization the breakfast was held. The Hubbard medal of the Geographic Society was awarded by Comdr. Richard Evelyn Byrd, the latest recipient, while Porter Adams, president of the Aeronautic Association, announced that Col. Lindbergh, already a member of that body, from now on would be an honorary member.

A “frozen” camfollower, which prevented the valve in one of the cylinders of the Spirit of St. Louis’ engine from functioning, was the cause of Col. Lindbergh abandoning his beloved ship and accepting the offer of F. Trubee Davison. Assistant Secretary of War for Aviation, of any type of Army Air Corps plane he desired.

Chooses Pursuit Plane.

The former Army flying cadet chose a pursuit ship and, explaining that he always had wanted to fly with the first pursuit group of Selfridge Field, the Army’s crack fighting outfit, declared he felt honored to be able to lead such an organization to New York.

The pursuit group of 21 planes, which flew here from Detroit to participate in the aerial welcome to the airman, was augmented by six Army observation planes, making a formation of 27 planes, with Col. Lindbergh flying in the lead.

Through cheering throngs, which packed the lobby of the Mayflower Hotel and the Seventeenth street entrance, Col. Lindbergh, accompanied by the three “air Secretaries,” Mr. Davison, William P. MacCracken, Jr., of the Department of Commerce, and Edward P. Warner of the Navy, climbed into a White House automobile and was whisked through the city with a police escort and followed by 65 automobiles, bearing airmen and members of the official reception committee.

The speeding caravan went south on Seventeenth street, east on Pennsylvania avenue, down East Executive avenue behind the Treasury and out Pennsylvania avenue to Eleventh street southeast. Here the procession turned and followed the direct route to the air base.

Cheered Walking to Plane.

Col. Lindbergh was officially welcomed to the station by Lieut. Comdr. Homer C. Wick, the commanding officer, and his staff and escorted direct to the Spirit of St. Louis, which had been set out in the rear of seaplane hangar No. 2 and roped off. A small crowd, privileged to gain admission, applauded the tall flyer as he walked along at a brisk pace, clad in the pin stripe blue suit and gray felt hat.

Col. Lindbergh swept his eyes over the airplane and between handshakes made an examination of the cockpit. He expressed himself as being ready to go, so Aviation Chief Machinist’s Mate William J. Morris, who commanded the crew of mechanics that set up the plane, climbed in and started the engine. Morris let the engine idle for a few moments until sufficient temperature had been obtained and then Col. Lindbergh climbed in, felt hat and all.

Instantly a gleam of satisfaction and composure swept over his face as he pushed forward on the throttle and increased the revolutions of the engine. He increased the speed of the propeller until it was nearly “full out.” Then the engine began to “pop” at intervals, and he slowed it down. Again he “gave ’er the gun” and the “popping” continued. Finally he “cut the gun,” shut off his switches and waited while two Navy mechanics climbed to the top of the engine and began unscrewing spark plugs. They found the plugs to be in good condition, and this meant that a deeper search would have to be made.

In the meantime the 21 planes of the 1st Pursuit Group and the six observation planes from Bolling Field had taken the air and were cruising about the field, waiting to pick up the Spirit of St. Louis. Col. Lindbergh began to get restless, bearing in mind his “heavy date” with New York City.

When it appeared that a valve was jammed and that several hours of labor would have to be expended to right this defect, Mr. Davison offered Col. Lindbergh the plane. The airman made his decision in a second, climbed out of his plane, boarded the White House automobile and sped around to the Army side of the field, followed by a long string of automobiles.

Already a large crowd had gathered at the Army side to see the take off, and they were a happy lot to see the airman at close quarters. Capt. C. F. Wheeler, operations officer of the field, knew nothing about the switch in planes until Col. Lindbergh arrived on the field. One of the new Curtis pursuit ships, with engine cold and resting in a hangar, was pounced upon by a crew of mechanics, rushed out to the line and started. Hardly had Col. Lindbergh been able to reach it than the powerful 425-horsepower engine was running at almost full throttle.

“Flying Gear” Borrowed.

Everything was in readiness to take off when Maj. R. L. Walsh, Army Air Corps and White House aide, assigned to assist Col. Lindbergh, discovered there was no ‘‘flying gear.” A rush was made to the flying-clothes locker of the operations office and the outfit of Lieut. Bob E. Nowland, adjutant of the post, and almost as tall as Col. Lindbergh, was confiscated, much to Lieut. Nowland’s delight, together with a parachute.

The flying “gear” consisted of a blue and gold knit stocking cap, helmet effect, fitting close to the head and over the ears of Col. Lindbergh; a pair of the latest type aviation goggles, a dark-brown leather “wind-breaker” and the chute.

They fitted the airman to perfection. The mechanic jumped out of one side of the Curtiss P-1-A pursuit plane and Col. Lindbergh climbed in the other. He adjusted himself, once more appeared contented, threw open the throttle and, satisfied with the roar of the engine and the instruments recording its every throb, was wheeled about and taxied down the field.

The group had been in the air almost an hour. They had been cruising about and their powerful engines ate up nearly 20 gallons apiece of the precious fuel. Some of the planes were not as heavily fueled as the others and they came in to land. As the group travels and operates as one plane, all ships came in for a landing.

For awhile it appeared that Col. Lindbergh would not be able to get into the air until the entire group had been refueled. A gasoline truck rushed out and poured the fuel into one or two of the planes and then everything was ready.

Suddenly Roars Down Field.

Col. Lindbergh, in his trim, powerful, yet highly sensitive fighter, had been waiting down at the south end of the field, next to the plane of Maj. Thomas G. Lanphier, commander of the group. His engine was idling all the while, and spectators kept their eyes trained on it. Suddenly and without a signal from any one, he threw open the throttle and roared down the field. Scarcely had the wheels left the ground when he pulled up into a zoom that startled the large crowd of airmen present.

With bated breath they watched him, hoping he would “cut the zoom” ‘ any moment. But, as some airmen afterward said, “Lindy knew what he was doing” and he kept the stick pulled back against his body while the propeller pulled the heavy weight up to two hundred, three hundred and finally four hundred feet before Col. Lindbergh flattened out.

A sigh of relief went up from the crowd when he got on even keel. There is no question about the young man’s ability to fly any type of plane, especially the difficult pursuit craft, as he was graduated from a year’s intensive training at Kelly Field, Texas, as a pursuit pilot. His flying speed was on the ragged edge of a stall, as it were, and he would not have had sufficient momentum to flatten out or turn.

That type of take-off has been done before, but it is not being done in routine fashion. Col. Lindbergh had seen the plane a few minutes yesterday but at that time he did not know he would use it. This morning he had sat in it about 10 minutes, with idling engine, waiting for the pursuit group to get ready, and in that time he had learned to place explicit confidence in its engine and performance ability. Hence his daring take-off.

“Stunts” a Little.

Up in the air about 700 or 1,000 feet the pilot cruised a bit and suddenly he flopped over into a right-hand barrel roll. In making this maneuver the wings revolved about the fuselage which served as an axis. It was a little rough, but it must be remembered that Col. Lindbergh had not engaged in any stunt work for more than a week and as each plane has its own peculiarity, he had to get acquainted with it on the controls.

This right hand roll was soon followed by a left hand roll which was much smoother and then the pilot settled down to circling over the field.

The group by now was taking off in flights of three planes each—not in Lindbergh fashion, however, but in long graceful climbing turns. Soon Maj. Lanphier and his 20 birds together and the formation of six observation planes hung on behind. Seeing the escort in order, Col. Lindbergh struck out for New York and by 9 o’clock his tiny plane had faded into obscurity.

=====

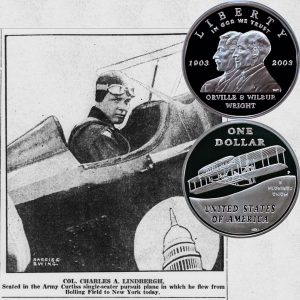

The First Flight Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an image of Col. Charles A. Lindbergh in the Curtiss pursuit plane.