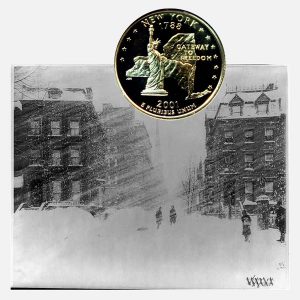

Today, the New York State Quarter Coin remembers the storm that crippled the northeast, especially New York City. It began as rain on Sunday, March 11, 1888 but quickly became much more.

From the New York Tribune newspaper of Tuesday, March 13, 1888:

=====

The forcible if not elegant vocabulary of pugilism supplies the phrases which will perhaps, best reveal to the popular imagination the effect of the storm that visited New-York yesterday. New York was simply “knocked out,” “paralyzed,” and reduced to a condition of suspended animation. Traffic was practically stopped, and business abandoned. The elevated railway service broke down completely, but not without supplying a tragedy to the history of the day; the street cars were valueless; the suburban railways were blocked, telegraph communications were cut; the Exchanges did nothing; the Mayor didn’t visit, his office; the city was left to run Itself; chaos reigned, and the proud, boastful metropolis was reduced to the condition of a primitive settlement.

The wind and the snow did it all. There have been before in New York winds that have howled louder and sped faster and snowfalls heavier and deeper; but never before, not even in the memory of that most astute disciple of Ananias—”the oldest inhabitant”— such a terrific combination of wind and snow.

To say that March exhibited the lion-like qualities, with which it is usually credited, would be a weak slander. March yesterday wasn’t a lion merely; it was a whole howling menagerie.

The mischief began brewing on Sunday with drizzling rain and gusty winds, which steadily increased in force. The rain gave way to snow ten minutes after midnight, and then the wind lashed itself into fury and howled wrathfully. Newspaper men going home in the “wee sma’ hours o’ the morning” found progress difficult. To avoid getting “stalled” the trains on the Third Avenue Elevated Railroad skipped the intervening stations between Chatham Square and Ninth-st, and Ninth-st. and Thirty-fourth-st., and so on until the terminus was reached.

When the city awoke, it was staggered and amazed. Great rifts of snow that kept shifting and twisting were piled up at the doors; sidewalks and streets were invisible, the air was filled with sleet and fine pellets of hail, which, impelled by the forces of the wind, pinched and stung like hot needles and clouded the vision with what looked like clouds of white smoke. The consequent discomforts began early. The milk and bread for the morning breakfast were frequently missing, because the milkman and the baker were unable to make their rounds. To add to the disagreeableness of stale bread and coffee without milk, the morning newspaper, on which the head of the family so often vents his spleen, was frequently missing.

But not until the door was opened did the man of business started downtown, did he fully realize what sort of a visitor it was that had taken possession of the town and was roaring through it. If not a man expert in definitions he at once declared that it was a “blizzard.” Generally he had not ploughed his way ten steps through the snow before he found that appellation too weak, and strengthened it with some profane expletive. The snow itself would have been had enough, but the wind made it a hundredfold worse, whisking it hither and thither and defying all efforts of snow, plough or shovel to clear a path anywhere. It was bitter cold. The fine particles of snow formed cakes of ice on beard and mustache, and even transformed the eyelashes and eye-brows Into ridges of ice. A few minutes of exposure to the storm transformed every bearded man into facsimiles of the children’s patron saint, Santa Claus.

Getting downtown proved to most people who essayed it an insurmountable task. In the earlier hours of the morning here and there a street car might have been seen lurching like a ship in a storm behind four or eight horses, with no room inside for the traditional “one man more.” But early in the day the street car people generally abandoned the battle against the elements and did not resume it until the storm had abated something of its violence.

On the elevated railroads matters were worse than on the streets, and it is certain that some result of the storm will be to start a “boom” for Mayor Hewitt’! underground scheme. The elevated trains proved a “delusion and a snare” a trap for the unwary traveler—for they were often compelled to come to a standstill between stations, and stop there for hours, where there was no getting out of them except at expense of life and limb. While the storm was raging no train got through under three or four hours, and for the greater part of the day no elevated trains ran.

Most of the people who succeeded in getting downtown had to foot it. Only the favored of fortune could avail themselves of the other alternative and endure the extortion of some mercenary and merciless Jehu. Fabulous prices were demanded and often paid for carriage hire. To walk any distance required a good deal of “bull dog” persistency and good powers of endurance. Not a few did it at the expense of frost-bitten ears. Umbrellas were useless. No expertness could prevent them being “inside out” in short order, for the wind shrieked and howled around corners without any regard for passers by.

The snow was uneven and treacherous and the wind prevented it from packing. Drifts varied in height from two to three, four, and even five feet, and they never remained long in one place, for the demon of the storm was more urgent and peremptory than was ever any blue-coated minion of the law in keeping things moving.

To add to the difficulty of locomotion was the danger of getting one’s legs snarled up in the wrecked telegraph, telephone and electric light wires that were plentifully strewed about. But worse of all was the sleet that congealed upon the eyelids and made it frequently as impossible to see where one was going as though in the midst of a London “pea-soup” fog. As a result, collisions between pedestrians were frequent, though the results were always accepted good-naturedly.

To anyone who ventured abroad on a tour of observation nothing was more noticeable than the spirit, of good humor that prevailed everywhere. It was eminently characteristic. Under similar circumstances the Briton would have grumbled persistently and volubly. But the American simply laughed at every mishap and discomfort and made light of it. And to anyone in good health there was a heap of fun in this plunging through snow-drifts and defying Old Boreas to do his worst. But his ruder blasts often compelled one to cling to a telegraph pole or a lamp post until their force was spent.

Of course many sign posts and awnings were wrecked, and the pedestrian who was luckless enough to let his hat go in the clutch of the storm frequently found pursuit hopeless. Numberless were the smaller discomforts and inconveniences occasioned. It often happened that clerks and others who succeeded in reaching their stores or offices found that those to whose keeping the keys had been entrusted had got “stuck” somewhere on the way. Then their plight was a sad one; it was hard to decide whether it was best to wait or strike out for home again. The only shops that did any business of any consequence were the grog shops, the cigar shops and the “gent’s furnishing” stores, where ear muffs and such protectors from Arctic weather were sold. The storm stopped the work of the law courts; the legal mill ceased to grind and for a day offenders went “uwhpit of Justice,” though the goddess stuck to her perilous post on top of City Hall.

Sad was the plight of many who had come into the city on the earlier suburban trains and when they started homeward learned that there were no trains. To make matters worse when they hurried to the telegraph offices to send reassuring messages to their wives and families, they were frequently told that the wires were “down” und there were no “communications open.”

Many people rather than put up with the discomfort of a return uptown on foot, stopped for the night at downtown hotels. Taken all in all it was a unique experience for New York, one that New Yorkers will talk about for many a day. Up to 8 o’clock, two feet of snow had fallen. The average velocity of the wind for the day was thirty-five miles an hour and its greatest force at any time was forty-two miles an hour.

====

The New York State Quarter Coin shows with an image taken during the blizzard of 1888.