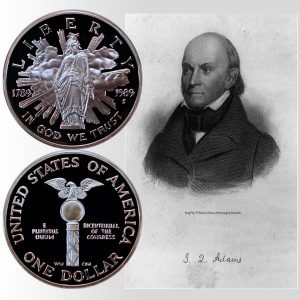

Today, the Congress Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers when ex-President John Quincy Adams arrived to take his seat in the House of Representatives on December 5, 1831.

From the booklet John Quincy Adams and Speaker Andrew Stevenson of Virginia, An Episode of the Twenty-Second Congress, collected by the Massachusetts Historical Society and published in 1906:

=====

March 4, 1829, Mr. Adams was succeeded in the presidency by Andrew Jackson, and retired to private life.

At the November election of the following year (1830) he was chosen to represent the Massachusetts congressional district known as the Plymouth district, and, as he wrote at the time, then became “a member elect of the Twenty-second Congress.”

Thus drifting back, as he expressed it, “amidst the breakers of the political ocean,” he established a precedent, — an ex-President reappearing in public life as a member of the popular legislative branch of that government of which he had recently been the executive head.

The Twenty-second Congress met December 5, 1831, and Mr. Adams then took his seat.

Andrew Stevenson, of Virginia, an administration or Jackson Democrat, was the same day elected Speaker by the House of Representatives, he having also been Speaker in both the two previous Congresses.

His principal opponent was Joel B. Sutherland, of Pennsylvania, also a Jackson Democrat, “both,” as Mr. Adams wrote, “men of principle according to their interest, and there is not the worth of a wisp of straw between their values.”

Mr. Adams voted for John W. Taylor, of New York.

The humorous side of the situation, so far as the new member from Massachusetts, quoad ex-President, was concerned, almost at once became apparent.

First chosen Speaker in December, 1827, as the candidate of an intensely bitter opposition to the Adams administration, in forming the committees of the present House, Mr. Stevenson plainly did not know what to do with the ex-President.

With no precedent for its disposition, he had an elephant on his hands.

In view of his long and varied diplomatic experience and his eight years’ tenure of the State Department, the proper place for Mr. Adams was obviously on the Committee on Foreign Affairs.

To be named second upon that committee would perhaps, in the case of an ex-President, be regarded as infra dignitatem, but the chairman of that committee should clearly be in sympathy with the administration, which the ex-President was not.

On the contrary, that no personal relations existed between General Jackson and Mr. Adams was notorious.

So, after full reflection, Speaker Stevenson had evidently reached the conclusion that he could not appoint Mr. Adams on the one committee to which he ought to be assigned.

Where then could a placement for him be found?

A new member and counted in the opposing minority, he must yet be a chairman, and, if anyhow possible, chairman of an important committee.

The times were troubled; the great issues were over the tariff and the United States Bank, with nullification an incident to the first.

Though the great debate between Webster and Hayne had occurred just two years before (January, 1830), Calhoun, the apostle of nullification, still occupied the vice-presidential chair, while South Carolina was the following November (1832) to embody the new heresy in an ordinance.

The “tariff of abominations,” so called, passed in 1828, in the administration of J. Q. Adams, and consequently approved by him, was the prolific source of discord.

This fact seems to have suggested to Speaker Stevenson a way out of his quandary. He availed himself of it.

He appointed the ex-President chairman of the Committee on Manufactures, upon which committee, under the system of reference then in congressional vogue, would devolve the difficult task of dealing with the issues which the defiant attitude of South Carolina towards a protective tariff was rapidly forcing to the front.

The assignment was, under the circumstances, at best obviously embarrassing; but Speaker Stevenson took good care in no way to ameliorate its asperities.

The committee was composed of seven members; of the six beside the chairman, one only was in political accord with the ex-President; the remaining five were all Jackson Democrats, and, as such, had been his more or less bitter political opponents.

Three of the six had sat in the preceding Congress; three were new members.

So far as Mr. Adams was concerned, the arrangement was courteous; for Speaker Stevenson it was apparently an adroit escape from an awkward situation.

Mr. Adams, however, seems to have heard the announcement with something closely resembling dismay.

He at once recognized the position as one of high responsibility, and, perhaps, of labor more burdensome than any other in the House; but, he wrote, it is “far from the line of occupation in which all my life has been passed, and [a position] for which I feel myself not to be well qualified. I know not even enough of it to form an estimate of its difficulties. I only know that it is not the place suited to my acquirements and capacities.”

Brought up in contests incident to the development of the idea of independence and, subsequently, of the rights of neutrals, involved in fierce controversies and intricate diplomatic entanglements growing out of the wars of Napoleon and the national hunger for territorial expansion, J. Q. Adams was no economist or financier.

Questions of that class did not appeal to him, nor did he grasp their bearings.

To such an extent was this the case that our associate Mr. Stanwood asserts that during Mr. Adams’s administration no mention is found of the tariff in any of his messages to Congress; and, in one of the debates now about to take place, he made an “astonishingly naive remark” in which he referred to what had been one of the chief bones of contention in the tariff debates during his own administration as something of which he had only recently become advised.

General Jackson even, Mr. Stanwood further tells us, “had been supported in the North as a staunch tariff man, more earnest in the cause of protection than Mr. Adams.”

From the time of his return to America after the Peace of Ghent absorbed in official studies and duties, he had found, as he freely admitted, no time left in which to “pursue the progress of the Science of Political Economy.”

He had, he confessed, never looked into “Ricardo’s book,” and “knew nothing even, of Malthus’s Definitions.”

And now he heard his name suddenly announced as chairman of the House Committee on Manufactures!

What did he know about manufactures? About tariff schedules, what?

Nevertheless, he forthwith proceeded with characteristic devotion to apply himself to the work in hand; and, so doing, he developed almost at once another humorous side, even if the humor of it was to him not apparent.

In his new situation “amidst the breakers of the political ocean,” — he was brought into sharp collision with his own Secretary of State of four years before when the Tariff of Abominations was enacted, for Mr. Clay, now in the Senate, was the recognized leader of the opposition, and its presidential nominee.

When the two met at the Capital for the first time, both newly come back into public life, — the late Secretary in the upper legislative chamber, the ex-President in the lower, — Mr. Clay good-naturedly asked of Mr. Adams how it felt, this “turning boy again to go into the House of Representatives”; and on Mr. Adams telling him that so far the work was light enough, Clay repeated several times that when the House got to business, Mr. Adams would find the “situation extremely laborious.”

The only comment on this made by Mr. Adams was — “that I knew right well before.”

=====

The Congress Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image of John Quincy Adams, circa mid-1830s.