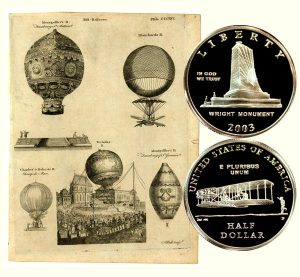

Today, the First Flight Commemorative Half Dollar Coin remembers an early attempt at flying a hot air balloon on July 17, 1784 in Philadelphia.

In the Life of John Fitch: The Inventor of the Steam-boat by Thompson Westcott, published in 1857, the author described Mr. Fitch’s complaints about the public’s focus of the day.

“In one of these complaints, he laments that mankind should neglect so important a work as the steam-boat, whilst they run mad about ‘beloons and fireworks.’ ”

The author provides an example of the excitement around one of the balloons:

=====

Balloons, fireworks, and steam-boats were equally objects of attention about this time, and they fairly divided the public wonder between them as matters of curiosity, but of no real utility.

Of the three, steam-boats were least cared about. Balloons and fireworks enjoyed a certain share of popularity, but steam-boats were subjects of derision.

The allusion of Fitch was caused by circumstances which could not escape the attention of anyone who watched the signs of the times. The first successful ascent with an aerostat in the United States (it is believed) was made in 1784, by Mr. Carnes, of Maryland.

He brought his balloon to Philadelphia, and an ascent was announced to take place on the 17th of July, in that year, from “the new work-house yard.”

The balloon was of flimsy silk, having holes in some places, and being patched in others with bed-tick. It was without a proper net-work, and the power which was to raise it was not gas, but heated or rarified air.

To render this fire-balloon successful, it was necessary to have a stove with fuel to burn in the mouth or neck of the machine, so as to keep the air rarified. The furnace thus employed weighed one hundred and fifty pounds.

The aerostat was thirty-five feet in diameter, and it was supposed it would carry four hundred and nine pounds.

On the appointed day the fire was kindled, the silken sphere expanded, and the cords being cut, the machine slowly ascended. The air blew it against the prison-wall. Mr. Carnes was brushed against it, and fell to the ground.

This was a lucky disaster; for the balloon soon afterwards caught fire, and was consumed. The stove fell in South street, near the old theatre.

Undaunted by this failure, some of the town philosophers proposed to raise subscriptions to construct a larger balloon, sixty feet in diameter, and capable of raising 3373 pounds. This scheme never came to fruition.

The next wonder was the steam-boat; which, by those who remembered Carnes’ failure, was placed in the same category.

In 1792, the celebrated Blanchard came to Philadelphia, and with pompous flourish announced his intention of making his forty-fifth ascension. He took up considerable space in the newspapers, and had a tact in skillfully inflaming public curiosity equal to the latter-day cunning of our most renowned showmen.

M. Blanchard chose the jail-yard — or “prison- court,” as it was politely called — for his place of exhibition.

He was addressed, or affected to have been addressed, by various persons, for the honor of participation in the trip.

To these he made replies through the newspapers, declining company, upon account of having only brought 4200 pounds of vitriolic acid with him — a quantity only sufficient to enable him to effect one ascension by himself.

He said that enough vitriol to justify him in taking up another person could not be had in Philadelphia, and that to buy it would cost one hundred guineas.

He proposed to receive subscriptions, at five dollars each; but finding that there was not much alacrity in embracing the opportunity, he agreed to issue tickets for inferior places at two dollars each.

He estimated that five hundred first-class subscribers would be necessary to pay the expenses, and was ready to issue one thousand second-class tickets.

The 10th of January, 1793, was appointed for the ascension.

President Washington was present at 9 o’clock, and Fisher’s artillery fired fifteen guns in honor of his appearance.

From that time until the ascent, two guns were fired every fifteen minutes.

Within the yard the audience was small, but outside it was immense. At five minutes past 10 o’clock, Mons. Blanchard, attired in a blue dress, wearing a cocked hat with a white feather, stepped into a blue and spangled car, attached to cords covering a balloon of yellow silk.

General Washington handed him a paper, and spoke a few words. The cords were out, the band struck up a lively air, and Mons. Blanchard went up, waving the American and French flags.

In forty-six minutes the aeronaut safely descended near Woodbury, N. J., shortly afterward was brought back to the city, and immediately called upon the President to pay his respects.

The affair, as a pecuniary enterprise, was represented to be a failure. One of the newspapers of the day apologized for the fact in this wise:

“Great numbers who had neglected to purchase tickets were afflicted with considerable regret at not having been immediately present in the Prison Court, to see the preparations and witness the undaunted countenance of the man who thus sublimely dared to soar through the regions of air.”

Much adulation was expressed of a similar kind. The following lines, in French, appeared in the newspapers:

“Great Blanchard, as you wing your way towards the heavens, announce to all the planets of the universe that Frenchmen have conquered their interior enemies, and that those without have been repulsed by their intrepidity. Dart through Olympus, and tell the gods that Frenchmen have been victorious. Implore the aid of Mars, that the arms of France may crush the ambitious designs of tyrants forever.”

Another flatterer said, “Franklin, with a firm grasp, dared to seize the lightning in the immensity of space where it is formed. Blanchard, bold in his flight, visits those regions. He traverses them as his conquest. The glory earned by the courage and ingenuity of the French Philosopher is not eclipsed by that which the intrepid sagacity of the American Philosopher merited.”

One Joseph Ravara, Consul General for Genoa, who was represented to have been a great traveler on land and water, besought the honor of adding a new distinction to his character as a voyager by a flight in the regions of air.

He addressed M. Blanchard publicly, offering to take up subscriptions to reimburse him. The latter did not object. The finale of the matter was, that M. Blanchard announced that he had received for the sale of tickets, $400; subscriptions, $263; total, $663. His expenses he represented to be 500 guineas; so that he was $1580 out of pocket.

Mr. Ravara did not “go up,” but perhaps enjoyed as much distinction by an exhibition of his effigy, as large as life, at Bowers’ wax-work show, North Eighth street, above Market, seated, with a counterfeit figure of M. Blanchard, in a car suspended from the ceiling of the room, “the American and French flags in their hands, and having on their own clothes.”

M. Blanchard was honored by Governor Mifflin with the use of a portion of his lot on the north side of Chestnut street above Eighth. Here the Frenchman built a rotunda, and exhibited his balloon; but some rascals threw stones against it and broke the silk; so Mr. Ravara did not ascend.

Subsequently, on two occasions, Blanchard sent up a balloon with a parachute attached, having dogs and cats in the car, which was detached by an explosion, the animals descending safely to the ground.

In 1794, he advertised his willingness to make an ascension if it was possible to obtain twelve pipes, or cylinder tubes, six feet long.

With such apparatus, he said he could fill his balloon with gas in two days. It was very difficult to get such work done in this country, but a proprietor of an iron-furnace undertook to do it.

On the faith of this contract the aeronaut announced his forty-sixth ascension, but a day or two afterwards postponed it, declaring that an experimental trial had shown the pipes and castings to be worthless.

He then gave notice that he would cease all further attempts at aerostation in this country, “until the arts are brought to such perfection as to furnish him the means necessary to success.”

Blanchard exhibited in his Rotunda models of balloons and mechanical contrivances.

The following advertisement, published in August, 1793, is so curious that it is worthy of preservation:

A CURIOUS CARRIAGE.

Mr. Blanchard, adopted citizen of the principal cities in Europe, Pensioner of the French Nation, Member of several Academies, &c, &c, has invented a carriage which runs without the assistance of horses, and goes as fast as the best post chaise.

An Automaton in the shape of an eagle, chained to the tongue of the carriage, and guided by the traveler, who holds the reins in his hands, directs it in every respect.

This extraordinary carriage cannot only travel on all roads, but likewise ascends any mountain which is accessible to any common carriage.

The distance it may proceed is unlimited, as there is no springs in the case that require winding up.

Monday, the 26th August, at half past five o’clock, at his Rotunda, on Gov. Mifflin’s lot, Philadelphia, Mr. Blanchard will make two experiments; the one of Natural Philosophy, and the other of Mechanism.

An air balloon of 11,498 cubic feet will be filled with Atmospheric Air in the space of six minutes, (instead of ten hours, which were required formerly,) by the help of a Machine which he has invented, and but lately brought to perfection.

The Eagle fixed to the carriage beginning its flight, the carriage will come out from it, stand and run round the place, carrying two persons.

The entrance is half a dollar, the door will be opened at five o’clock, and the experiments begin precisely at half past five.

Gentlemen who have dogs accustomed to the chase are requested not to bring them along, as experiment has shown that they may prove very dangerous to the eagle, which imitates nature to perfection.

Note. — Select parties, who wish to see this experiment by themselves, will please to apply to Mr. Blanchard, at The Rotunda, who will be happy to satisfy the curiosity of amateurs.

The allusion made by Fitch to “Fireworks” was caused by the success of several foreign artists who had given exhibitions in Philadelphia.

Among the names of these, the most deserving of preservation are Michael Ambroise & Co., whose claims to remembrance are founded upon the interesting fact that they were the first who manufactured inflammable gas and exhibited gas-lights in America.

They had an amphitheatre in Arch street between Eighth and Ninth, where they frequently displayed their fireworks.

In August, 1796, they advertised an exhibition of fireworks, one part composed of combustibles in the usual style, the other of “inflammable air, by the assistance of light,” as “lately practiced in Europe.”

Of the latter they formed “an Italian parterre,” “a picture of the mysteries of Masonry,” “a view of a superb country seat,” “a grand portico,” etc.

There were eight pieces of these gas illuminations; and as they must have been produced by bending pipes in the required forms, we may suppose that Messrs. Ambroise & Co. were ingenious artists and mechanics at a time when the arts in this country were yet in a very rude state.

=====

The First Flight Commemorative Half Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image of several balloon designs, circa 1784.