Today, the Washington State Quarter Coin remembers the return of George Francis Train from his round the world trip begun on March 18, 1890 and ended May 24, 1890 at a small brass plate in Tacoma.

Excerpts from Washington, West of the Cascades by Herbert Hunt and Floyd C. Kaylor, published in 1917:

=====

From its earliest days Washington has taken a lively interest in what may be termed spectacular advertising “stunts.” Pacific City, Chehalis City and Port Angeles were boomed at a time when printer’s ink was little used for advertising purposes.

The Snoqualmie Pass lottery and the Tacoma townsite advertising came later and used considerable newspaper space and then in 1890 came “Citizen” George Francis Train and his “Around the World in Sixty Days” for the Tacoma Ledger.

Mrs. R. F. Radebaugh, wife of the owner of the Ledger, was in Boston when Nellie Bly returned from her 72-day race around the world. Train had been writing some of his peculiar “Vander-Billion Psychos” for the paper and Mrs. Radebaugh wrote him a note of thanks for some manuscript he had sent her.

Taking a menu card from the restaurant table before him Train, with the Nellie Bly story running through his mind wrote Mrs. Radebaugh a reply closing with the words:

“Why not sell theater for $1,000 lecture, and I will go around the world in sixty days.”

Mrs. Radebaugh at once wired to her husband and next day received a reply offering Train $1,500 to make the trip. This offer was accepted and the starting date fixed for March 16th.

The Tacoma Theater had been opened on January 13th. It had been a notable event and the newspapers had devoted great space to describing the theater- then the largest in the state — and the performance of the latest comic opera “Paola” by the J. C. Duff Comic Opera Company especially engaged for the occasion. Choice seats had been sold at auction and it was from the newspaper story doubtless, that Train obtained the idea of giving a lecture for the benefit of the ’round the world trip.

…

At 4 P. M., March 14th, Train arrived in Tacoma in a drizzling rain, but this did not keep the people from crowding Pacific Avenue to greet him. Train, Radebaugh, Isaac W. Anderson and Mayor Wheelright rode up Pacific Avenue, led by the united bands of the city, with one hundred instruments. At the Tacoma Hotel a great crowd awaited. It perhaps was fortunate for the distinguished visitor that he had adopted the rules of never shaking hands.

When the curtain of the Tacoma Theater went up on the evening of March 15th, and General Sprague introduced Citizen Train to the audience there was just $4,158 in the treasury, but the house was not full. He asked that the foot lights be turned low, as he himself would furnish the gas. His lecture was a spicy potpourri of reminiscences of his life as a boy, railroad builder, writer, lecturer and traveler and was frequently interrupted by laughter and applause. The next two evenings he lectured in Germania Hall to large audiences.

Those were busy days. The merchants outfitted Train with shoes, shirts, hand bags, purses, pencils, etc. Captain Fife superintended the laying of the 4×15-inch brass plate from which the start was to be made in front of the Ledger office on C Street. Patton’s four gray horses were groomed and cared for as perhaps no horses were ever groomed and cared for before and everything was placed in readiness for the start.

Shortly before 5:30 on the morning of March 18th Train was at the starting place. The carriage, in which Radebaugh and Sam W. Wall, who was to accompany Train, were seated, stood at the curb. Isaac W. Anderson, Col. Clinton A. Snowden and Captain Fife, the official timekeepers, stood, watches in hand, awaiting the firing of the 6 o’clock gun by Captain Bixler, of the bluff. Citizens lined both sides of the route to the wharf where the Olympian, groaning with a full head of steam, lay with her nose pointed down the bay. And then the shot rang out.

Train leaped from the brass plate into the waiting carriage, the driver lashed his team and down C Street to Ninth, down Ninth to Pacific and down Pacific to the wharf went the traveler on the first lap of his journey, while the splinters of the planking flew from the feet of the racing team. Whistles screeched, bells clanged, the crowd shouted and danced, and ran pell-mell in pursuit of the carriage. The old cannon boomed its salute from the hill. Three seconds behind the carriage carrying Train came that of the time keepers.

In six minutes all were aboard the steamer, Wharfinger Keene and Captain Clancy had cast off the lines and in a moment Captain Roberts had the Olympian under way. Des Moines was passed at 6:44, Seattle at 7:36 and at 11:30 the Abyssinia was sighted making her way down from Vancouver. At 1:22 she hove to in the Royal Roads off Victoria. Train and Wall were transferred while Frank Ross made a speech and broke a bottle of wine over the liner’s bow. At 1:45 the Abyssinia resumed her journey toward the Pacific.

The first message received from Train came in a bottle, thrown overboard March 20th. The bottle drifted into the straits. A Makah Indian found it and took it to the Neah Bay salmon cannery and it was brought to Tacoma by Nels Oberg. Upsetting precedents, smashing records and tilting at established customs were favorite pursuits of Train. When a second message reached Tacoma containing the single word “Connected,” it was translated to mean that the traveller had made connection with the Hong Kong boat; but there was nothing to indicate how it had been done. Yokohama was reached on Good Friday — a holiday — every bank, government office and most of the business houses were closed. Rousing Herr Leopold, agent of the North German Lloyd line, out of bed, Train informed him that he must catch the steamship General Werder. The agent told Train that the ship had sailed two days before and was then at Kobe.

“Kobe!” said Train. “That is about 300 miles down the coast and can be reached by rail? When will she sail from there?”

“Tomorrow morning,” replied Leopold.

“Tomorrow morning” meant a twenty-four hour railroad ride, in addition to the time needed to obtain passports. Train told the agent that he must hold the boat. Leopold said it was impossible. Train however overrode his demurrers, and Leopold telegraphed orders to hold the ship.

No traveler was permitted to leave the empire without passports. Train was told that he must see the American minister, Mr. Swift, at Tokio, thirty miles away, and that at least three days would be required to get the papers. “Three days to sign a paper!” exclaimed Train. “It is time that I reduced the limit to three minutes!”

Away to Tokio he hastened where he found the minister, who saw the emperor, and when the afternoon train for Kobe left Yokohoma, Train and Wall with their passports were aboard. Japanese red tape never was unrolled so quickly as on that Good Friday when the Train typhoon struck the coast.

Next day the travelers boarded the German steamship. Hong Kong, Singapore, Colombo, Aden, Port Said were passed and Brindisi, Italy, reached. From Brindisi through Paris to Calais, by rail, across the channel to Dover and by rail through London to Holyhead, across the Irish Sea to Dublin and down to Queenstown and the Atlantic, went Train and Wall pell mell, gathering interesting baggage as they went, including a rare collection of hats. Close connection was made with the steamship Etruria and six days later, the travelers reached American soil at New York.

The first thing Train said to the newspaper men who went out in a tugboat to capture the traveler and bring him ashore, was to ask about the special train he supposed would be awaiting him. Here he met disappointment. He had gone around the world on a hop, skip and jump; he had held up steamships already on their way, had chartered boats, had made flying leaps from “rickshaws” to sampans, from tugboats to the decks of ocean liners and here he was at New York with no special train awaiting to carry him to Tacoma.

It was expected, of course, that Train would return West on the Northern Pacific Railroad which came to its western terminus, Tacoma, direct, and when it was announced that he was to travel on the Union Pacific there was wonderment all over the country.

For thirty-six hours Train and Wall waited while New York publishers printed a carload of newspapers containing a full account of the trip. The car was attached to a train carrying a party of newspaper reporters, railroad men and the two world girdlers, and the run across the United States was under way.

At Hood River, Ore., a bridge had burned and the party left the train, crossed the charred frame work and boarded a freight caboose for Portland.

There was no special train there, as had been expected, and Citizen Train went into the ticket office, threw his overcoat down on a seat and went to sleep. That was indeed almost the last straw. Train had feared it and had sent a telegram to Tacoma saying: “Provide a special train in Portland. Don’t let me lie five hours in a town that has been calling me names for twenty years.”

Five hours later he started for Tacoma. At Centralia a crowd of Tacomans met him but he was disappointed and retired to his seat without heeding the cheers. In the hour required to reach Tacoma balm was applied to his hurt feelings, but Train continued to ask, “What does it mean?” At Huntington, Ore., he had lost his pocket book, ticket and money, a loss he did not discover until he tried to pay for a banquet given to the newspaper men of the party.

This was the climax to many irritations. In Tacoma the train was greeted with the firing of cannon and parades, bands and cheering multitudes. Many invitations to dine were pressed upon him, but Train replied:

“I’ll eat nothing until I see Radebaugh. Where would we be if he had had two legs broken?”

Secretary Snowden accompanied the traveler to Wapato Lake. With just what ointment Radebaugh salved the troubled soul of the Citizen is not known, but the next morning Train announced he would have breakfast.

After comparing all the guesses submitted as to the time required by Train to make his trip, the time keepers, Isaac W. Anderson, W. J. Fife and C. A. Snowden decided that F. S. Learned, of Boisfort, Lewis County, was entitled to the free ticket for a trip around the world. Learned’s guess was 67 days, 16 hours and 42 minutes. The time made by Train was 67 days, 12 hours, 59 minutes and 55 seconds. Nicoli Brunn, of Chicago, guessed 67 days, 9 hours and 33 1/2 seconds. The ’round-the-world ticket had a value of $661.

Sam W. Wall wrote an interesting book describing the 22,040-mile journey. His analysis showed that Train’s average speed the hour, while traveling, was fourteen miles. The average by land was thirty-three miles and by water eleven miles. Wall formed a great admiration for his “chief,” as he called him, and his book was written in a spirit of much kindliness to the “Solitaire.”

=====

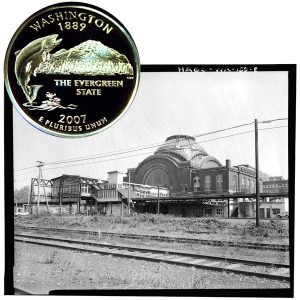

The Washington State Quarter Coin shows with an image of a Tacoma train station, circa 1930s.