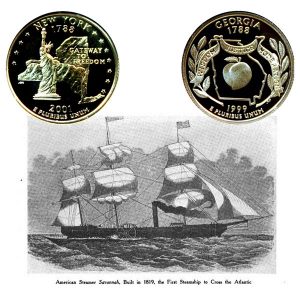

Today, the New York and Georgia State Quarter Coins remember when the first transatlantic steamship, the Savannah, left the port of the same name heading for Liverpool, Copenhagen and St. Petersburg 198 years ago.

From the International Marine Engineering of May 1919:

=====

The honor of first navigating the sea with a steamer belongs to Colonel John Stevens, of New York, and the credit is not diminished by the fact that he was forced to it by circumstances beyond his control.

Having built the steamboat Phoenix, he was prevented from navigating the Hudson, because at that time (1808) Fulton and Livingston had a monopoly of this river, and accordingly the Phoenix was sent around by sea to the Delaware River.

England in those days was very active and ambitious in the new enterprise, yet it was nine years later before she ventured on sea voyages.

In 1817 the steamer Caledonia first crossed the Channel on her way to Holland. Transatlantic steam navigation was long discussed before anyone combining sufficient skill with courage and a spirit of adventure made the bold attempt.

The Times (of London. England), in the issue of May 11, 1819, thus announces the expected event:

“Great Experiment. — A new steam vessel of 300 tons has been built at New York for the express purpose of carrying passengers across the Atlantic. She is to come to Liverpool direct.”

On the very day that this brief notice appeared, the vessel referred to was visited by the President of the United States and made a short trial trip previous to her departure on a hazardous voyage.

This steamer, named the Savannah, the first that crossed any of the oceans was built at Corlear’s Hook, New: York City, by Crockett and Fickett.

The New York custom house records give her measurements as follows: Tonnage, 319; length. 98 1/2 feet; beam, 26 feet: depth of hold. 14 1/2 feet.

The Savannah was equipped with an inclined, direct-acting, low-pressure engine of 90 horsepower. It had a single 40-inch cylinder: the machinery was built by Stephen Vail at Morristown, N. J., and the boiler by Daniel Dod at Elizabeth, N. J.

Originally intended for a New York and Havre packet, the Savannah was purchased before completion by Scarborough and Isaacs, merchants of Savannah.

She was launched August 22, 1818. She could carry only seventy-five tons of coal and twenty-five cords of wood.

Commanded by Captain Moses Rogers, and navigated by Stevens Rogers, both of New London. Conn., the Savannah sailed from the city of Savannah, Ga., on May 22, 1819, bound for St. Petersburg via Liverpool.

She reached the latter port on June 20, having used steam eighty hours out of the twenty-six days, and thus demonstrated the feasibility of transatlantic steam navigation.

The original log-book of the Savannah, containing the daily record of her memorable voyage, is in possession of the United States National Museum. There are no original pictures extant of the Savannah. A crude lithograph is the basis of all the pictures published of this historic vessel and is here reproduced.

It is to some degree faulty, but is the best that can be had. Some authorities, notably the late S. W. Stanton, maintained that her paddle wheels were not open, but had canvas paddle boxes.

There exists an oil painting showing the Savannah so fitted. The question, however, is doubtful.

On one page of the Log occurs the statement: “We took the wheels in on deck in 30 minutes.” This statement refers to the fact that the steamer was so constructed that in case of boisterous weather her paddle wheels could be brought in on deck.

According to the Log the steamer reached Savannah from New York on April 6, having used steam four days. It remained there eight days and then “got steam up and started for Charleston,” which was reached next day.

The vessel lay at Charleston until April 30, when it returned with steam to Savannah.

The Savannah remained twenty-three days at the city of the same name, and on May 11 was visited by the President of the United States.

The Savannah was fitted with accommodations for passengers, and, although the Savannah Georgian advertised her departure some days ahead, no venturesome travelers presented themselves.

Crossing the Western ocean by steam was then too much in the nature of an experiment.

On May 22, Captain Rogers “got steam up and at 9 A. M. started” on the transatlantic voyage.

Nothing of much interest is detailed in the daily records of the log-book, which are, on the whole, rather monotonous.

On June 2 they “stopped the Wheels to clean the clinkers out of the furnice, a hevy head sea, at 6 P. M. started Wheels again; at 2 A. M. took in the Wheels.”

Land was sighted on June 16, being the coast of Ireland, and on the 17th the Savannah “was boarded by the King’s Cutter Kite, Lieutenant John Bowie.”

The log-book here, as elsewhere, is sternly brief, but fortunately we have in Stevens Rogers’ own words a fuller account of the amusing circumstances connected with the boarding by the King’s cutter.

He said, in a communication to the New London (Connecticut) Gazette: “She [the steamer] was seen from the telegraph station at Cape Clear, on the southern coast of Ireland, and reported as a ship on fire.

“The Admiral, who lay in the Cove of Cork, dispatched one of the King’s cutters to her relief. But great was their wonder at their inability, with all sail in a fast vessel, to come up with a ship under bare poles.

“After several shots were fired from the cutter, the engine was stopped, and the surprise of her crew at the mistake they had made, as well as their curiosity to see the singular Yankee craft, can be easily imagined. They asked permission to go on board, and were much gratified by the inspection of this naval novelty.”

Two days later (June 20) they “shipped the wheels and furled the sails and run into the River Murcer, and at 6 P. M. come to anchor off Liverpool with the small bower anchor.”

These simple words are all that were thought necessary to record the successful termination of the daring venture: not a word of boasting, of congratulation, nor even of thankfulness, does this man of deeds place on record.

Fortunately, we have details of the manner in which the steamer was received in the account given by Stevens Rogers already alluded to.

He says: “On approaching Liverpool hundreds of people came off in boats to see her. She was compelled to lay outside the bar till the tide should serve for her to go in.

“On approaching the city, the shipping, piers, and roofs of houses were thronged with persons cheering the ad venturous craft. Several naval officers, noblemen and merchants from London came down to visit her. and were very curious to ascertain her speed, destination and other particulars.”

During the sojourn of the Savannah at Liverpool the British public regarded her with suspicion, and the news papers of the day suggested the idea that “this steam operation may in some manner be connected with the ambitious views of the United States.”

One journal, recalling the fact that Jerome Bonaparte had offered a large reward to anyone who would succeed in rescuing his brother Napoleon from St. Helena, surmised that the Savannah had this undertaking in view.

The steamer remained twenty-five days at Liverpool and sailed for St. Petersburg on July 23, “getting under way with Steam,” and “a large fleet of Vessels in company.”

Captain Rogers touched en route at Copenhagen, where his vessel excited great curiosity, and also at Stockholm, where she was visited by the royal family, or, in the homely language of the log-book, “His royal highness Oscar Prince of Sweden and Norway come on board.” (August 28.)

While at Stockholm, we find this entry: “Mr. Huse [Christopher Hughes] the American minister and Lady and all the Furran Minersters and their Laydes at Stockholm come on board” — and at Mr. Hughes’ invitation made an excursion among the neighboring islands.

On September 5 the steamer left Stockholm, with Lord Lynedock, of England, who was then on a tour through the north of Europe, as a distinguished passenger.

On the 9th she reached Cronstadt. having used steam the whole passage, and a few days later she arrived at St. Petersburg.

Here she was visited, at the invitation of our ambassador at that court, by the Russian Lord High Admiral, Marcus de Travys, and other distinguished military and naval officers, who also tested her superior qualities by a trip to Cronstadt.

The Savannah lingered at St. Petersburg until October 10 and then set sail on her homeward voyage, “in company with about 80 sail of Shiping.”

She arrived at Savannah Tuesday, November 30.

Shortly after, the steamer was taken to the navy yard at Washington. The object of this visit to the national capital was, in the words of another, “to fix her name and exploits in the minds of prominent men from all parts of the United States, in order to lay a foundation for the defense and maintenance of our claim to that distinction which this craft and her daring commander had unitedly wrought out for our nation upon the mighty deep.”

The subsequent history of the Savannah can be told in a few words.

On account of the great fire in Savannah, her owners were compelled to sell her. The engine was removed and she was purchased to run as a packet between that place and New York, whither she was bound, under charge of Captain Nathaniel Holdredge, when she was lost on the south side of Long Island in November, 1821.

This sketch of the voyage of the Savannah, with the extracts from the log-book, establishes beyond a doubt that America deserves the credit of having been the first to apply steam machinery to the navigation of the Atlantic.

Many articles on the early history of steam navigation have been written which ignore the claims of the Savannah and her enterprising captain.

In fact, when the steamers Sirius and Great Western arrived in New York Harbor April 23, 1838. twenty years after the exploit of the Savannah, they were received with extravagant manifestations of delight: and in an editorial in the New York Express of April 24, reference is made to the “unusual joy and excitement in the city, it being almost universally considered as the beginning of a new era in the history of Atlantic navigation.”

The achievement of the Savannah was forgotten, her skillful captain no longer lived to claim his rights, but patriotic citizens protested in the public press against losing sight of the just claims of America.

=====

The New York and Georgia State Quarter Coins show with an artist’s portrayal of the first transatlantic steamship Savannah.