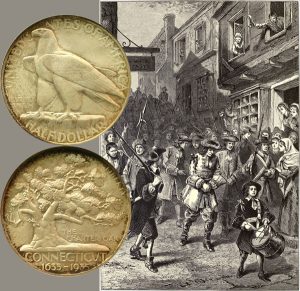

Today, the Connecticut Tercentenary Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin remembers the story of the charter and when it was retrieved 328 years ago.

From Hartford in History, A Series of Papers by Resident Authors, edited by Willis I. Twitchell and published in 1899:

=====

Sir Edmund Andros, having established his authority at Boston, wrote Governor Robert Treat, of Connecticut, December 22, 1686, saying, “I am commanded and authorized by His Majesty, at my arrival in these parts, to receive in his name the surrender of your charter, if tendered by you.”

Thereupon the General Assembly wrote a letter to the Earl of Sunderland, Secretary of State, which proved to be the most important document in their case, for though it expressed a preference for union with Massachusetts as a final resort, it was construed in England, and designedly no doubt, to be a “request of being annexed to the Bay” and hence a surrender.

This it surely was not. Andros did not so interpret it. He continued his measures to “induce” the colonists “to make surrender” as he had been instructed to do. The delivery of their charter as an act of surrender would have answered his purpose instead of a vote.

Our Connecticut fathers were resolved not to do either. They would submit if they must, but never surrender.

Having, however, an order from the government, based upon a misinterpretation of the above letter, Andros set out for Hartford, October 26, 1687, to assume authority.

Some gentlemen of his council, and sundry blue-coats, trumpeters and red-coats made up his escort.

The town of Hartford at this time was only a scattered village, having about 1,200 inhabitants. Its taxable estates amounted to only £18,118, though it was the wealthiest town in the colony.

In the General Assembly it was naturally influential, having in that body Major John Talcott, Captain John Allyn, Ensign Nathaniel Stanley and Mr. Cyprian Nichols; and the most of the rest being in one way or another connected with Hartford families.

Throughout the colony the sentiment was strongly averse to a surrender of the charter, as the documents show, but there were some who foresaw the final issue and questioned the wisdom of a contest. Among these were Major Talcott and Captain Allyn, the secretary.

This opinion, which they expressed to the Assembly, March 30, 1687, called forth another and decisive vote against surrender. Doubtless also this awakened suspicion concerning them, for at the meeting on the 15th of June, sundry of the court desired the charter brought into their presence, which apparently satisfied them as to their faithfulness as keepers.

The secretary, however, made such a record as to excuse himself if it did disappear, for he wrote: “The Governor bid him put it into the box again and lay it on the table, and leave the key in the box, which he did forthwith.”

It was useless, these men saw, to urge expediency upon the freemen of Connecticut, committed to an obstinate affection for their charter.

It must have been toward night, the 31st of October, when Governor Andros, having traveled that day from Norwich, crossed the river at Wethersfield ferry and with the escort of the county troop entered Hartford, where he was greeted with becoming honors.

Some conference was held that evening between him and the General Assembly in their chamber — the second floor of the meeting-house.

We are sure they were a serious company of Connecticut fathers who sat by candle light about the royally- attired Sir Edmund.

He only wanted a vote or an act of surrender!

What happened?

Trumbull says: “The charter was brought and laid upon the table.

“The lights were instantly extinguished, and one Captain Wadsworth, of Hartford, in the most silent and secret manner, carried off the charter and secreted it in a hollow tree.

“The candles were officiously re-lighted, but the patent was gone.”

Such is the tradition, which he recorded a century ago. So far back as 1780 the tree was known and then “esteemed sacred ” as that in which the charter was concealed.

Every schoolboy knows where it stood before the Wyllys mansion.

Governor Roger Wolcott, who was then nearly nine years old and had distinct recollections of other matters of that time, who also had every opportunity to learn the truth later, in 1759 wrote in his memoir:

“They ordered the charters to be set on the table, and, unhappily or happily, all the candles were snuffed out at once, and when they were lighted the charters were gone.”

He told President Stiles, five years later, that Nathaniel Stanley took one charter and John Talcott the other “from Sir Edmund Andros in the Hartford meeting-house, the lights blown out.”

Our historians are agreed in the belief that Connecticut’s charter was hidden in the famous oak at some time during that troublesome period.

When this hiding occurred, which charter was hidden and who hid it, are nuts of that Halloween night for the historians to crack.

The natural harmony of accounts and traditions is, that Stanley, who was an active promoter of the revolution in 1689, took the original charter in the darkness and Talcott passed the duplicate out to Wadsworth, not then a member of the Assembly.

Either charter may then have been hidden a short time in the oak standing near the mansion of one of the authorized keepers.

Some think that this hiding occurred the previous June, when the Secretary left the charter on the table as ordered.

One or the other may have been later in the keeping of Andrew Leete, of Guilford, as the tradition is.

The colonial records show that Wadsworth secured the duplicate charter in that “very troublesome season ” and was thereafter the custodian of it, for which “faithful and good service” he was rewarded in 1715 with twenty shillings.

It is certain that on the evening when some superstitious persons were wont to believe that “devils, witches and other mischief-making beings are all abroad,” the charter of Connecticut was spirited away, and it was not Sir Edmund Andros who did it.

Most important is it for us to note that the sentiment of Hartford must have been strong against any surrender to have made such a daring procedure of one or more of its townsmen possible or safe.

Which of the charters was the original?

The other was the duplicate and the one once in Captain Wadsworth’s keeping.

In a legal sense both may have been so regarded. The surrender of either would have answered the purpose.

The one at the Capitol is now so considered, and may have been received as such a few years after the Revolution on account of its well-preserved condition.

As to which was the original in the historical sense, the clue is found in the meaning of the words “Pr fine five pounds,” which were appended to one, as proven by several early manuscript copies.

The Historical Society has a certified “Copy of the original charter remaining in the Secretary’s Office,” October 30, 1782, which has these words.

As they are lacking in the charter at the Capitol, they must have been on the fragment with the Historical Society.

It is now determined by the entry in the accounts of the clerks who received the payments for patents, that this clause noted the fee on the original charter and not the price of the duplicate.

Therefore the Historical Society has the one which was first brought over and accepted by the freemen, and if Wadsworth hid the one he secured in the oak it was that now framed in the Capitol.

Whatever may have been the story of this fragment, it was brought to light by a pupil of the Hartford Grammar School, in 1817, who saw the mother-in-law of the South Church minister about to put it into a bonnet. It had been given her by the daughter-in-law of George Wyllys.

He rescued it and years afterwards found out what his old parchment was.

This youth was John Boyd, in 1858 elected secretary of Connecticut.

At the time the charter was hidden no one supposed it would ever be revived.

Those who did it in no wise thought they had thus saved their government, but only themselves from a surrender.

Andros assumed authority, commissioned magistrates and united Connecticut to the dominion of New England. After two years, however, a revolution came on. He was imprisoned at Boston, and finally sent home to England.

Meanwhile William and Mary ascended the throne.

Then Connecticut, on the 19th of May, 1689, brought out its sacred charter and resumed its former government.

His Majesty graciously allowed this continuance of their “rights and privileges,” which were judged in law not to have been invalidated; and although repeated attempts were made later to have the charter revoked, it stood until 1818, when it was made the basis of the new constitution.

=====

The Connecticut Tercentenary Commemorative Silver Half Dollar Coin shows with an artist’s image of the Boston Revolt and the downfall of Sir Edmund Andros.