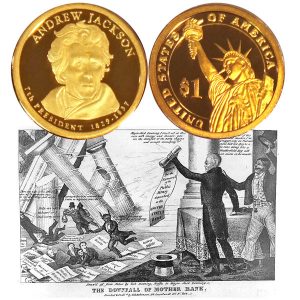

Today, the Jackson Presidential $1 Coin remembers the senate’s censure of Andrew Jackson on March 28, 1834.

The censure debates began in December, however the actual resolution did not occur until 183 years ago.

The reason? Simply, Jackson removed the federal funds from the National Bank.

From the American History Briefly Told compiled by the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration of La Crosse, Wisconsin, published in 1912:

=====

Jackson’s presidency will forever be remembered in history for three things:

(a) The introduction of the Spoils System;

(b) the crushing of Nullification in South Carolina;

(c) the discontinuance of the United States Bank.

We have seen that Jackson’s political views at the time of his election were unknown even to his supporters. It soon became evident, however, that the new President

(1) favored strict construction of the Constitution, and consequently,

(2) opposed internal improvement at national expense, protective tariffs, and the United States Bank.

…

We may remember that:

(a) The first United States Bank was planned and chartered by Hamilton for twenty years (1791-1811);

(b) it failed to be re-chartered in 1811 and, consequently, ceased to exist for five years;

(c) it was finally re-chartered in 1816 for twenty years longer (1816-1836);

(d) its object was to found a solid and uniform currency, and to assist the government in managing its financial affairs.

Jackson, like most other Democrats, believed:

(a) That the United States Bank was unconstitutional;

(b) that it enriched its managers at the expense of the people;

(c) that it had grown corrupt and dangerous to the freedom of the country, because of its powerful influence in politics, since its funds were used to reward its friends and punish its enemies.

The bank was advantageous to the people in as much as the money paid the government was not withdrawn from circulation.

But this advantage was overbalanced by the fear that the Bank might at any time exercise an overwhelming power in politics, which it actually did in the campaign preceding Jackson’s re-election, when it used money to bring about the defeat of the President.

Upon Clay’s urgent advice, the friends of the Bank now brought matters to a crisis by introducing into Congress a bill to re-charter it for twenty years longer (1832), though the old charter would not expire till 1836.

After a heated discussion, lasting five months, the bill passed both houses of Congress.

Jackson, however, promptly vetoed it, giving as reasons that it was an “unnecessary, useless, expensive, un-American monopoly, always hostile to the interest of the people, and possibly dangerous to the government as well.”

Naturally, the campaign cry for 1832 was “Jackson or the Bank.”

Jackson was re-elected President (1832) by an overwhelming majority over Henry Clay, the great leader of the of National Republicans. Martin Van Buren of New York was made Vice-president.

The presidential campaign of 1832 gave rise to our first national convention and party platform (a written statement of party views). Before this, presidential candidates were named by a congressional caucus or by state legislatures.

1. The Anti-Masonic party, whose aim was to keep Freemasons out of office, really originated our national conventions. They met and named William Wirt for President (1831); this party carried only the state of Vermont and soon after disappeared.

2. The National Republicans next met in convention and unanimously nominated Henry Clay for the presidency. They made the first platform ever issued. This platform declared the views of the party as favoring protection of American industries, internal improvements, and a United States Bank, and denounced the Spoils System, or practice of turning men out of office for political differences.

3. The nominees of the Democratic convention were, as we have seen, Jackson for the presidency, and Van Buren for the vice-presidency.

Secret societies in connection with the revolutionary organizations and clubs of France, had already been formed during the elder Adams’ administration.

These were succeeded by the Freemasons. The murder of a certain William Morgan, who had threatened to reveal the secrets of the order, had caused great excitement and gave rise to the Anti-Masonic party.

Jackson, regarding his re-election as an approval of his anti-bank Jackson policy, determined to give the Bank a final blow.

He promptly ordered (1833) the Secretary of the Treasury to remove the government deposits from the Bank. The Treasurer refused to do so and was removed from office.

Roger B. Taney, appointed in his place, gave orders for the removal of deposits. Subsequently,

(a) the government gradually withdrew its money from the Bank to pay its debts;

(b) future deposits, instead of being made in a National Bank, were placed in certain state banks, situated chiefly in the South and West.

These banks, selected not so much for their soundness as for their political influence, came to be known as “pet banks.”

Meanwhile, state banks, termed “wild-cat banks”, were springing up on every side, increasing within eight years from three hundred twenty-nine to seven hundred eighty- eight in number.

Hundreds of these, having no capital at all, received deposits, and flooded the country with their notes, called “rag money .” People could now borrow money more easily than ever before.

This “wild-cat banking” gave rise to even wilder speculation, which extended to every branch of trade, but especially in the western states and territories.

Eager to grow rich, people bought government lands at perhaps a dollar or two an acre, expecting to sell them at enormously increased rates, particularly if located near imaginary towns laid out in the wilderness or along routes of proposed railroads or canals.

There was a general rise in prices. Everybody was borrowing, in order to buy and sell and grow rich. What if the banks should fail and their paper money become worthless?

Jackson became greatly alarmed, and determined to protect at least the United States Treasury against unsound money. Against the advice of the Cabinet, he quickly issued (1836) his celebrated “Specie Circular,” by which he ordered the land agents to receive only gold and silver in payment for government land.

The effects were immediate. The great demand for gold and silver necessarily created a scarcity of this coin, and the country was flooded with worthless paper money, termed “irredeemable currency.”

A crash was inevitable, but before it came, Jackson retired from office, confident that the “Specie Circular” would restore prosperity.

Congress, after many heated discussions, continuing during three months, finally adopted a resolution censuring Jackson for his action toward the National Bank. The President replied in a letter that, as the chief magistrate, he was independent of both Congress and the Supreme Court.

Some years later, Jackson’s party, led by Thomas Benton, having gained control of the Senate, crossed out the vote of censure from the Journal of that body.

Jackson’s anti-bank actions have been most harshly criticized; still we now believe that he did the country a valuable service in discontinuing the National Bank, for such a monopoly, absolutely controlling the moneys of the people, would ultimately prove detrimental to the interests of the nation.

The Bank of the United States, having ceased to be a government institution after its charter had expired (1836), continued as a State bank under a charter from Pennsylvania.

=====

The Jackson Presidential $1 Coin shows with an artist’s portrayal of the Downfall of the Mother Bank, circa 1833.