Today, the Missouri State Quarter Coin remembers when the earthquake began in New Madrid, 205 years ago.

From the Youth’s Companion of August 8, 1912, an excerpt of the article, “The Earthquake Year On The Mississippi” by George Cary Eggleston:

=====

The accounts that have reached us of what happened are by no means such as we should have of a catastrophe of the kind occurring in this day of newspapers and telegraphs, but fortunately many of those who endured the experience took pains to record their impressions of it, and still more fortunately, one or two of them were calm and careful observers, in spite of the terror to which they were subjected. As a result, it is possible to give an accurate account of the catastrophe a hundred years after its occurrence.

One of the calmest and most accurate observers was W. L. Pierce, who very soon after his escape from the earthquake region wrote a minute account of his experiences, that was published in the New York Evening Post, and is preserved to this day in a few of the great libraries. His account was written on Christmas, just nine days after the occurrence.

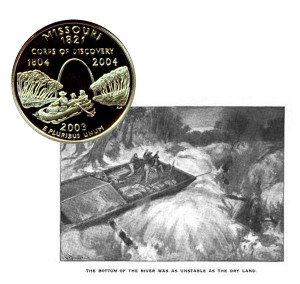

Pierce was floating down the river in a flatboat that had reached New Madrid Bend, seventy miles or so below the mouth of the Ohio, when the first shock came at two o’clock on the morning of Monday, December 16, 1811. It manifested itself first In rapid blows on the bottom of the boat, blows so severe that they threatened completely to destroy the craft.

Three shocks, coming in rapid succession, lasted for eight minutes. They were terrible minutes. Large oak-trees were broken in two like dry twigs. Other great trees were up rooted, and in Pierce’s phrase, “rushed from the forests, precipitating themselves into the water with force sufficient to have dashed us into a thousand atoms.” The banks of the river everywhere gave way; here they slid into the stream, there they were upheaved into enormous piles of earth, like the works of a great fortress. Great chasms were opened in the earth, some of which continued to yawn threateningly, and others of which closed up again as suddenly as they had opened.

The bottom of the river was as unstable as the dry land along the shores. In places where the water had been many fathoms deep, the bottom was suddenly upheaved until only mud-flats remained. In other places, where there had been scarcely any water at all, a channel was instantly formed, so deep that no lead-line on board the flatboats could fathom it.

From the deep river-bed dead and half-petrified trees, that had lain hidden there for ages, were thrown high into the air, and falling back, planted themselves, often upside down, in the mud.

Meanwhile the waters of the river seemed to be boiling; here and there the gases escaping from beneath sent up huge waterspouts that might have wrecked even a steamship. These explosions forced up great masses of mud, sticks and refuse, often as high as thirty feet above the surface of the water.

On shore the explosions, blowing the earth aside, left great cavernous, conical holes, precisely such as an explosion of dynamite far beneath the surface might create. From these holes sulphurous gases flowed, and filled the air almost to the point of suffocation. In the river sulphurous streams, often hot enough to make the whole river warm, flowed out like the gushings of a geyser.

Perhaps the best indication we have of the violence of the convulsions is furnished by Mr. Pierce, who says that in one instance he saw a forest tree with a trunk three feet thick torn up by the roots from the place of its growth, hurled bodily more than a hundred yards, and dropped into the river, where its roots embedded themselves so firmly in the mud that the tree stood upright in the water, quite as if it had always grown there.

As has been said, the first three shocks lasted for eight minutes. Then, after a brief pause, they were followed by others that lasted, with very brief interruptions, for one hundred and sixty-eight hours. For nearly two full years after that, every day brought its disturbances, some of them as violent as the first ones.

New Madrid, on the river-bank, has always been regarded as the center of the disturbance —probably because there were no white men living very far west of the river. Scientific men who have studied the accounts that remain to us of the catastrophe are satisfied that the real center of it lay much farther west. However that may be, we know that the earthquakes extended all over southern Missouri and Illinois, western Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas and Alabama.

Not far east of the river a vast lake— Reelfoot— was formed almost instantaneously, and it exists to this day. It is about fifty miles long, two or three miles wide, and very deep. The land covered by it was densely wooded; to this day, when the surface of the water is placid, the submerged forest— petrified now— can be plainly seen in the depths.

Fortunately, there were then no cities in the region. Had there been, they would have been shaken down during that first eight minutes, with results more disastrous than any recorded in the history of earthquakes. No city could have withstood such shocks for even half a minute, and the people would have been crushed beneath falling walls before they could possibly have escaped.

Fortunately also, there were no houses of brick or stone, and none of the kind we call “frame,” for none of them could have endured the shocks. The only houses were log cabins, built of tree trunks notched together at the corners, and roofed with what the Western people called clapboards—a kind of shingle four feet long, riven out of the very lightest wood, and held in place by poles securely notched into the main timbers of the cabin.

These log cabins were of one story, usually only seven or eight feet high in their walls, and no architect ever designed any form of human dwelling better fitted to endure earthquake shocks. Yet so severe were the disturbances that even the log cabins were twisted and turned about and wrecked; their inmates fled from them in terror, and dwelt thereafter in bush shelters that could hurt no one, even if they should tumble down. All the small towns and villages were deserted; their inhabitants fled in terror from every structure that might be shaken to pieces. In one town there remained only one man— an old negro, who was too feeble to get away.

Safety, however, was not to be found even in the lightest of bush shelters, for in many places great chasms, opening in the earth engulfed the shelters, with those in them. Sometimes the fissures, shutting as suddenly as they had opened, closed their jaws on what they had swallowed.

The terror-stricken people had enough coolness left, however, to devise and adopt a means of protections against this danger, They observed the fissures nearly always ran in a certain direction. Accordingly, they felled great trees at right angles to that direction, and build their shelters on the trunks, in hope that they might serve to bridge any fissures that opened beneath them.

Panic was natural: but the people were brave, hardy and resolute, accustomed to meet danger without flinching. They were also accustomed to endure hardship without complaining, and to devise means for lessening it. So long as their bush huts, built upon tree trunks, gave reasonably safe shelter to their wives and children, they continued to cultivate their fields in spite of the fact that rifts were likely to occur in them at any moment.

Meanwhile the earthquakes continued. In the river many islands that had long been landmarks to the pilots of flatboats and keel-boats suddenly sank beneath the water and disappeared forever. Other islands, which remain to this day, were as suddenly heaved up from the bed of the river.

There is a tradition that one of these islands, rising from the depths of the river channel at the precise point where two flatboats, lashed together, were floating down the stream, lifted them up and held them hopelessly stranded. The flatboatmen waited several days for the river to return and float their craft again. Their cargoes consisted mainly of provisions, —bacon, eggs, onions, potatoes, corn-meal, and the like,— but as long as they hoped to set their boats afloat again, they refused to draw upon these supplies for their own support, because they belonged, not to them, but to other people. At last they gave up hope, broke up the flatboats, made a great raft of the timbers, placed the cargoes upon it, and feeding themselves from the provisions that they carried, started to float down to New Orleans.

But when they pushed their raft away from the mud bank and out into the channel their troubles were not over. To their consternation, they discovered that the river was running up-stream. Either some upheaval farther down the river, or some enormous sinking of the bottom farther up-stream had reversed the current. For three days and nights the raft continued to float slowly up the river. Then, after another shock, the current turned, and ran down-stream with a fury that for a time threatened to tear the frail raft to pieces.

The Mississippi River was at that time full of fish, most of which were large and some of which were of gigantic size. The hot water that here and there gushed up into the stream killed so many of them that all through that winter and the following spring dead fish floated constantly on the surface.

Then again there was the mud. In my boyhood a middle-aged man who had been in the New Madrid region during the earthquake year sat on a grassy bank overlooking the Ohio, and told us about his experiences, in homely but graphic phrase, which I think I can reproduce with accuracy. Certainly I can repeat the substance of what he said.

“You see I was a boy then, a long-legged fellow whose breeches were four inches too short, ’cause I’d grown faster than my breeches had worn out. Of course we were scared when the first shocks came, and we were a good deal worse scared when we found next morning that our cabin was twisted into a kind of diamond shape, with a strong leaning toward falling down, and all the clapboards a-shedding themselves off the roof like the hair of a horse in springtime.

“Well, we made a bush shelter, working sort of between the shocks, as you might say. When the shocks were actually on, we were giddy, just like a boy gets to be when he spins round on his heels too many times and too fast.

“Well, we got used to the thing after a while, particularly after the shocks got to be farther apart and not quite so strong as at first. Still, they were strong enough to make you jump out of your bed if you were asleep, and to make you stop your horse in the furrow if you were plowing, and they were frequent enough to keep you jumping a good deal of the time. We got used to it, but we couldn’t get over having the dizzy and sick feeling whenever a bad shock struck us. Then there was another thing. Sometimes when we were eating, a shock would come, and half the things on the table would be slid off into our laps. It was annoying — especially when the things to eat happened to be gravy or molasses.

“We got along pretty well, spite of it all, and when spring came we plowed and planted as best we could. I had taken up some land on my own responsibility, and in the odd times between work for my father I planted a long, narrow strip of low grounds in corn.

“By getting up at the crack of day, and sometimes plowing or hoeing by moonlight, after the chores were done, I kept that little patch of corn in mighty good condition, till one night, when the stalks were about ten inches high, there comes a shake, and a crack opened straight through my corn patch, lengthways. The crack wouldn’t have mattered so much if it hadn’t been for the mud that came up through it. It was very soft mud, and hot mud at that, and when it got through gushing up, there wasn’t a single stalk of my corn that wasn’t dead and buried. Things of that sort were kind of discouraging.”

Little by little the earthquake shocks diminished in frequency and violence. Little by little the sturdy pioneers rebuilt their cabins, although many of them did not venture to build on the ground, but still built on tree trunks. Little by little the region became quiet. The mud banks that had been upheaved in the river’s bed clothed themselves in greenery— with rushes and grasses at first, with bushes a little later, and with trees after a while, some of which have grown into forest giants during the hundred years that have since elapsed.

One of the phenomena that marked that terrible time endured for half a century afterward. As late as the fifties the Mississippi River was characterized by “boils,” as they were called— sudden upheavals of the water, in which no skiff could live for a minute, and in which the stoutest swimmer could not hold his own even long enough to be rescued. Sometimes these “boils” were so violent as to wreck flatboats that happened to be caught in them. Even steamboat pilots regarded them with respect as one of the dangers of navigation that they must avoid.

No doubt they were produced by the slowly diminishing earthquake disturbance, which found in the deep and soft bottom of the river the easiest outlet for gases that formerly had rent the earth itself asunder.

=====

The Missouri State Quarter Coin shows with an artist’s image of men on the Mississippi river during the New Madrid earthquake of 1811.