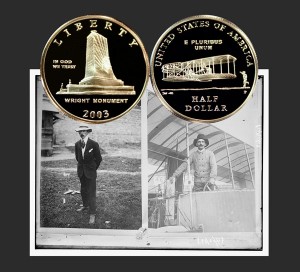

Today, the First Flight Commemorative Half Dollar Coin remembers the flying event of 110 years ago.

A short summary in the Aircraft Yearbook by Fay Leone Faurote, published in 1919, provided a summary of the flight:

=====

1906—September 13. Santos Dumont made the first officially recorded European aeroplane flight, leaving the ground for a distance of 36 feet, flying at a velocity of 23 miles per hour, used a cellular aeroplane, resembling a Hargrave kite; equipped with a 40-50 H. P. motor. Two wheels fitted to machine to permit “taking off” and landing.

=====

In his book, Aircraft of Today, A Popular Account of the Conquest of the Air, published in 1917, Charles Cyril Turner included a chapter titled “The First Aeroplanes” with mention of Santos Dumont’s short flight.

An excerpt follows:

=====

In 1893 Clement Ader made a full-sized steam-driven flying machine with flapping wings, but subsequently turned it into a monoplane, and on October 14, 1897, in the presence of representatives of the French War Minister, he flew 300 metres.

He relates that the surprising experience nearly caused him to lose his senses. The machine was wrecked in landing.

The spectators would not, or could not, induce the authorities to take the matter seriously, and Ader’s invention was ignored until, in the enthusiasm caused by practical flight achievements in 1908, it was remembered and placed in the Aeronautical Exhibition at the Grand Palais in December of that year.

In his disappointment at the coldness of its reception in 1897 Ader burned all the drawings, and would have destroyed the machine but for the solicitations of a friend who appealed to him on the ground of patriotism.

Lawrence Hargrave, an Australian, in 1898 and 1899, made some remarkable experiments with kites, and invented the cellular or box-kite.

The principal experimenters in kites who made ascents were Le Bris in 1856, Baden-Powell in 1894, Wise in 1897, and Cody.

The Farman and the first Santos-Dumont aeroplanes were based on the principle of the Hargrave box-kite.

Owing in very large measure to the promise afforded to aviation by the introduction of the light petrol motor, progress became rapid. It renewed men’s hopes, for early experimenters, like Maxim, had said, “Give us a light and powerful engine, and we will show you how to fly.”

In 1900 Wilbur and Orville Wright, of Dayton, Ohio, achieved better results than Chanute or any other predecessors.

They made gliders having twice as great a lifting surface as that hitherto employed.

In their first gliders the aviators took a horizontal attitude.

The work of the Wright Brothers is stamped upon aeronautics, and it is not necessary here to describe their experiments in detail. They attained extraordinary skill and experience in flight.

They made almost daily ascents during many years, keeping aloof from observation, and allowing it to be supposed that the rumors of their exploits were merely newspaper sensationalism.

Not until 1908 did these famous pioneers fly in public.

Ernest Archdeacon, in France, obtained some valuable results in 1905; and in February, 1905, in conjunction with the Aero Club of France, he held an exhibition of gliding apparatus and models of flying-machines.

Esnault-Pelterie at the same period was also making gliding experiments in France. But it will be sufficient to mention here a few of the more famous record flights at that interesting period in the history of aviation.

It was on September 13, 1906, that Santos-Dumont made the first officially-recorded European aeroplane flight, leaving the ground for a distance of twelve yards.

On November 12 of the same year he remained in the air for twenty-one seconds, and travelled a distance of 230 yards.

These feats caused a sensation, but comparatively few people realized that a new and wonderful era was being ushered in.

An Englishman deserves the credit for the next flight, although he made it in France on an entirely French machine.

This was Henry Farman, who, on October 26, 1907, flew 820 yards in fifty-two and a half seconds, and quickly followed with other flights, on July 6, 1908, remaining in the air for twenty and a half minutes. Leon Delagrange also was at this period making nights.

These experiments, however, were eclipsed in America by the Wright Brothers. Orville Wright accomplished a flight of over an hour’s duration as long ago as September 9, 1908, and on September 12 stayed up for one hour and fourteen minutes.

Then Wilbur Wright went to France and began his remarkable series of flights, often taking up passengers with him.

Half-hour and even hour flights were very common: and on December 31 Wilbur Wright flew for two hours and nineteen minutes, and all the world wondered.

Wright also demonstrated that pupils could become adept after spending a few hours in the air; and his pupils in their turn became teachers.

To Farman belongs the distinction of making the first cross-country journey in an aeroplane.

On October 31, 1908, he flew from Chalons to Rheims, a distance of sixteen miles, in twenty minutes.

From one achievement to another aviation made progress until, slowly, the public began to think there was ” something in it ” after all.

France was in advance of England in this respect, playing her usual enviable role of pioneering.

France’s record, as in the motor aerial motor industry, resulted in her taking the cream of the aerial motor and aeroplane industries, and securing a lead of many years.

In England nothing was done at all comparable with the achievements of the French and the Americans.

S. F. Cody, A. V. Roe, and two or three others were doing pioneer work, but the public took no interest.

Roe made the first flight in a British machine, Cody following closely with his biplane.

Towards the end of 1908 Moore-Brabazon bought a Voisin biplane, in which he made short flights in France.

Meanwhile, in Canada, Douglas McCurdy was making significant progress, and achieving results which compel us to place him next to the Wrights, who at that time had no serious rival.

The “Silver Dart” in which McCurdy made his trials resembled the Wright machine in that it had no tail.

The supporting surfaces had only a single concave curvature.

In various respects it resembled the Wright machine, having the elevator in front and the vertical rudder at the rear, but it was driven by only one propeller.

McCurdy made many demonstrations with his apparatus, and flights of half an hour were frequent.

The Canadian Government were so impressed that they decided to afford official help.

McCurdy was assisted by Baldwin, who made flights in the same apparatus.

Dr. Alexander Graham-Bell was experimenting on a totally different type of machine.

This was called the “Cygnet II,” and it consisted of some 3500 tetrahedral cells.

A small measure of success was achieved, but it was spoilt by accidents.

In the United States Glenn Curtiss constructed a biplane which, in some respects, resembled the Wright machine, and with it won laurels at the Rheims Aviation Meeting.

…

=====

The First Flight Commemorative Half Dollar Coin shows with images of Alberto Santos Dumont.