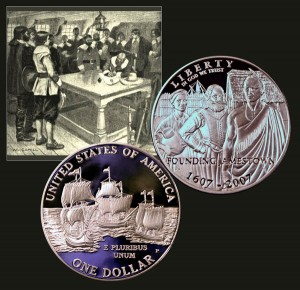

Today, the Jamestown Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin remembers those, even before the “Founding Fathers,” that began the embryonic stages for future American Liberty.

In the Barnes’s School History of the United States published in 1914, Joel Dorman Steele, Esther Baker Steele mentioned the first colonial assembly that became a foundation for the early colonists:

=====

Governor Yeardley believed that the colonists should have “a hande in the governing of themselves.”

In obedience to the company’s instructions, he called at Jamestown, July 30, 1619, the first legislative body that ever assembled in America. It consisted of the governor, the council, and two deputies, or “burgesses,” as they were called, chosen from each of the eleven settlements, or ” boroughs,” into which Virginia was then divided.

The privilege of self-government was afterwards (1621) embodied in a written constitution — the first of the kind in America — granted by the company under the leadership of Sir Edwin Sandys.

The laws passed by the colonial assembly had to be ratified by the company in London; but the orders from London were not binding unless ratified by the colonial assembly.

A measure of freedom was thus granted the colony, and Jamestown became a nursery of liberty.

=====

In 1907, Jamestown celebrated its tercentenary. On July 30, 1907, they gathered to also commemorate the early colony’s first legislative meeting.

At the celebration, Adlai Stevenson spoke honoring the occasion. In his book, Something of Men I Have Known published in 1909, he included the speech in its entirety.

An excerpt follows:

=====

The time is propitious for setting history aright. This exposition will not have been in vain if the fact be crystallized into history yet to be written, that the first settlement by English-speaking people — just three centuries ago — upon this continent, was at Jamestown. And that here self- government — in its crude form but none the less self-government — had its historical beginning.

Truly has it been said by an eminent writer of your own State, that prior to December, 1620, “the colony of Virginia had become so firmly established and self-government in precisely the same form which existed up to the Revolution throughout the English colonies had taken such firm root thereon, that it was beginning to affect not only the people but the Government of Great Britain.”

In the old church at Jamestown, on July 30, 1619, was held the first legislative assembly of the New World — the historical House of Burgesses. It consisted of twenty-two members, and its constituencies were the several plantations of the colony.

A speaker was elected, the session opened with prayer, and the oath of supremacy duly taken. The Governor and Council occupied the front seats, and the members of the body, in accordance with the custom of the British Parliament, wore their hats during the session.

This General Assembly convened in response to a summons issued by Sir George Yeardley, the recently appointed Governor of the colony.

Hitherto the colony had been governed by the London Council; the real life of Virginia dates from the arrival of Yeardley, bringing with him from England “commissions and instructions for the better establishing of a commonwealth.”

The centuries roll back, and before us, in solemn session, is the first assembly upon this continent of the chosen representatives of the people.

It were impossible to overstate its deep import to the struggling colony, or its far-reaching consequence to States yet unborn.

In this little assemblage of twenty-two burgesses, the Legislatures of nearly fifty commonwealths to-day and of the Congress with its representatives from all the States of “an indestructible union” find their historical beginning.

The words of Bancroft in this connection are worthy of remembrance: “A perpetual interest attaches to this first elective body that ever assembled in the Western world, representing the people of Virginia and making laws for their government more than a year before the Mayflower with the Pilgrims left the harbor of Southampton, and while Virginia was still the only British colony on the continent of America.”

It is to us to-day a matter of profound gratitude that these the earliest American lawgivers were eminently worthy their high vocation.

While confounding, in some degree, the separate functions of government, as abstractly defined at a later day by Montesquieu, and eventually put in concrete form in our fundamental laws, State and Federal — it is none the less true that these first legislators clearly discerned their inherent rights as a part of the English-speaking race.

More important still, a perusal of the brief records they have left, impresses the conviction that they were no strangers to the underlying fact that the people are the true source of political power, the evidence whereof is to be found in the scant records of their proceedings — a priceless heritage of all future generations.

And first — and fundamental in all legislative assemblies — they asserted the absolute right to determine as to the election and qualification of members.

Grants of land were asked, not only for the planters, but for their wives, “as equally important parts of the colony.”

It was wisely provided that of the natives “the most towardly boys in wit and the graces” should be educated and set apart to the work of converting the Indians to the Christian religion; stringent penalties were attached to idleness, gambling, and drunkenness; excess in apparel was prohibited by heavy taxation; encouragement was given to agriculture in all its known forms; while conceding “the commission of privileges” brought over by the new Governor as their fundamental law, yet with the liberty-guarding instinct of their race they kept the way open for seeking redress, “in case they should find aught not perfectly squaring with the state of the colony.”

No less important were the enactments regulating the dealings of the colonists with the Indians. Yet to be mentioned, and of transcendent importance, was the claim of the burgesses ” to allow or disallow,” at their own good pleasure, all orders of the court of the London Company.

And deeply significant was the declaration of these representatives of three centuries ago, that their enactments were instantly to be put in force, without waiting for their ratification in England.

And not to be forgotten is the stupendous fact that while the battle with the untamed forces of nature was yet waging, and conflict with savage foe of constant recurrence, these legislators provided for the maintenance of public worship, and took the initial steps for the establishment of an institution of learning.

It is not too much to say that the hour that witnessed these enactments witnessed the triumph of the popular over the court party; in no unimportant sense, the first triumph of the American colonists over kingly prerogative.

=====

The Jamestown Commemorative Silver Dollar Coin shows against an artist’s view of early colonists meeting to determine the rules and government.