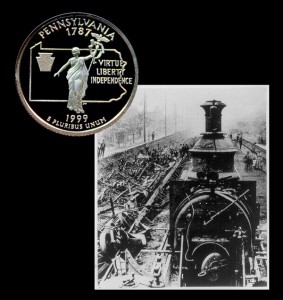

Today, the Pennsylvania State Quarter Coin shares some of the less violent portions of the great railroad strike of July 1877.

Col. Frederick L. Hitchcock wrote the following perspective in the History of Scranton published in 1914.

=====

The Riots of 1877. — Probably the most momentous event in the history of Scranton was the strike riots of August 1, 1877.

They were memorable in our history not only for the dire consequences in the loss of human life that grew out of them but as a most unexpected and unexplained after development of a great Nation-wide railroad strike, which for ten days had paralyzed the business of the whole country from the Atlantic to the Pacific, but which had passed over—a dying echo, so to speak, of that struggle which had destroyed millions of property and hundreds of lives in Pittsburgh and Reading, Pennsylvania, and other places.

The railroad strike had fallen like a thunderbolt out of a clear sky on July 23 previous, and within twenty-four hours not a railroad wheel moved east of the Mississippi, except on a few isolated lines.

For a week we had been cut off from all communication with the outside world, except by telegraph, and the primitive methods of transportation. Hundreds of passengers en route to their destinations were stalled here and at other places.

A discussion of the causes of the strike would be out of place here. Those who care to study those questions will find much material in Rev. Dr. Logan’s able book, “A City’s Danger and Defense.”

The following excerpt from the Scranton Republican of July 25, 1877, will give an idea of the condition of the public mind in Scranton and the strike situation:

The Great Strike. — Men in every calling seem imbued with the spirit of the great strike which has now assumed a national attitude.

The spirit of unrest impregnates the very atmosphere, and the contagion of discontent is borne on every breeze.

The community of Scranton was taken by surprise yesterday afternoon when they learned that the employees of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company had struck and events of a more stirring nature were hourly expected.

At the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company’s works there had been no notice, no premonition of the deep-seated disaffection which manifested itself shortly after twelve o’clock in the upper rolling mill, where the men at the sound of the gong left off work and retired from the place cheering.

They were peaceable and orderly, however, and marched in a body to the steel works, where they were speedily joined by the men employed at that place, and then proceeded to the machine shops, where a similar scene was enacted.

The men kept together, and were met by the general superintendent, Mr. W. W. Scranton, who happened to drive by where they were assembled.

Seeing the demonstration of which he had no previous notice he stopped and inquired the cause and was informed that the men were unable to work for the wages obtained and that they would not work unless the company reconsidered the recent reduction of the ten percent made in their wages.

Mr. Scranton admitted that the remuneration was small, but that in the prostrated condition of affairs the company could do no better.

He thought the men ought to have apprised him before taking such action as they did, but he could not promise any advance in wages just then.

Mayor McKune issued the following address:

To the Citizens of Scranton: — In view of the excitement throughout the country, occasioned by the labor troubles, and the lamentable loss of life and property in our own and other States, it becomes the duty of all good citizens to use their best efforts to preserve peace and uphold the law.

Recognizing, as everyone must, the unfortunate condition of the business and financial interests of all classes of the community, and especially the hardships and suffering of the laboring men, we must yet unite in maintaining to the fullest extent the majesty of the law and the protection of life and property.

I therefore earnestly urge all good citizens, and especially the working men themselves, to abstain from all excited discussion of the prominent question of the day.

The laboring men of our city are vitally interested in the preservation of peace and good order and prevention of any possible destruction of property.

I trust the leading men among the working men fully realize that the interests of the whole city are their interests and that any riot or destruction of life or property can work only injury to all classes and the good name of our city, and would by so much increase the burden of taxation.

In one day Pittsburgh has put upon herself a load that her taxpayers will struggle under for years.

In conclusion, I again earnestly urge upon men of all classes in our city the necessity of sober, careful thought and the criminal folly of any precipitate action.

Robert H. McKune, Mayor. Mayor’s Office, Scranton, Pa., July 24, 1877.

July 26, 1877 — The attempt on the part of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western railroad to run their regular morning train through to New York was frustrated by the crowd detaching the passenger and baggage cars on reaching Hyde Park.

They allowed the engine and mail car to go into the station and notified Mr. Halstead, superintendent, that the mails could go forward but nothing else. Mr. Halstead said in reply that the whole train must go or nothing.

The men then telegraphed Governor Hartranft their position and he replied as follows: “I have advised the superintendent to let the mail run through.”

Still Mr. Halstead refused, saying his company was only obligated to carry the mails on its regular passenger trains.

Obviously the striking men were desirous of avoiding interference with the United States mails.

Among the miners of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company the following action taken at a mass meeting held July 25, 1877, explains the situation from their standpoint:

Whereas, We, the employees of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Rail road Company, believe that we are not getting a just remuneration for our labor or a sufficient supply for ourselves and families of the common necessaries of life, therefore

Resolved, That we demand twenty-five per cent. advance on the present rate of wages; also it is further

Resolved, That with a refusal of these demands all work will be abandoned from date, as we have willingly submitted to the reduction and without a murmur or resistance and finding that it now fails us to live as becomes citizens of a civilized Nation we take these steps in order to supply ourselves and little ones with the necessaries of life.

A similar demand was simultaneously made upon the Lackawanna Iron and Steel Company by their mill and furnace employees. The following is Mr. Scranton’s reply:

July 25. 1877- Messrs. John Evans and others, Committee:

Gentlemen: — In reply to your request that the wages of men employed by this company be advanced twenty-five per cent. I have to say that nothing in the world would give me more pleasure if it were in my power to do so.

But I am sorry to say that with the present frightfully low prices of iron and steel rails it is utterly impossible for us to advance wages at all. Even at these low prices it is almost impossible for us to make sales.

Our steel works, as everybody knows, are now idle because we have no work to do there. Until the reduction of ten percent on the 10th of this month there has been no reduction in your wages for nearly a year, while during that time there has been a falling off in the prices we get for iron and steel of over twenty-five per cent.

I think you ought to consider these things fully and reflect whether the little work we can give you is not better than no work at all. I assure you when prices will warrant it we shall be very glad to pay wages in proportion.

Yours truly, W. W. Scranton, General Manager.

July 26, 1877 — Headline of Scranton Republican:

The Great Strike — A Comparatively Quiet Day. — The mob under control at almost all points. Passenger trains moving regularly on several roads. Representatives of commerce call upon the President to use force. Stagnation of business. Citizens enrolling for protection throughout the country. All quiet at Reading.

In the latter city the Philadelphia and Reading railroad had attempted by means of protection through a body of the company’s “Coal and Iron Police,” armed with Spencer repeating carbines, to break the strike, and a bloody collision with the mob had followed. The local militia had been called out. The result of the battle was twenty-eight casualties, of whom there were eight killed or mortally wounded.

The Grand Army of the Republic of New York tender their services to the Governor for the preservation of order and protection of life and property.

Headline of July 27, 1877:

The Great Strike—A Desperate Fight in Chicago.—The police attacked * * * Fifteen persons killed, a large number fatally and others seriously wounded. Riots in other sections.

July 31, 1877 — Local headline: End of the Railroad Strike. — The men vote unanimously in favor of work at the old wages. A committee informs Superintendent Halstead. Trains move in all directions. A peaceable ending of an orderly (?) strike.

=====

The Pennsylvania State Quarter Coin shows against a view of the damaged Pennsylvania Railroad of July 24, 1877.