Today, the Rhode Island State Quarter Coin celebrates the addition of Rhode Island as a state 225 years ago.

It was not an easy process for the Rhode Islanders with the final approval passing by just two votes.

The History for Ready Reference from the Best Historians, Biographers, and Specialists compiled by Josephus Nelson Larned and published in 1895 described Rhode Island’s post-revolutionary war struggles and the ultimate approval of the new federal constitution.

=====

Rhode Island emerged from the war of independence bankrupt.

The first question was how to replenish the exhausted treasury. The first answer was that money should be created by the fiat of Rhode Island authorities.

Intercourse with others was not much thought of. Fiat money would be good at home. So the paper was issued by order of the Legislature which had been chosen for that purpose. A ‘respectable minority ‘ opposed the insane measure, but that did not serve to moderate the insanity.

When the credit of the paper began to fall, and traders would not receive it, laws were passed to enforce its reception at par. Fines and punishments were enacted for failure to receive the worthless promises.

Starvation stared many in the face. Now it was the agricultural class against the commercial class; and the former party had a large majority in the state and General Assembly.

When dealers arranged to secure trade outside the state, that they might not be compelled to handle the local paper currency, it was prohibited by act.

When three judges decided that the law compelling men to receive this ‘money ‘ was unconstitutional, they were brought before that august General Assembly, and tried and censured for presuming to say that constitutional authority was higher than legislative authority.

At last, however, that lesson was learned, and the law was repealed. Before this excitement had subsided the movement for a new national Constitution began.

But what did Rhode Island want of a closer bond of union with other states ?

She feared the ‘bondage’ of a centralized government. She had fought for the respective liberties of the other colonies, as an assistant in the struggle. She had fought for her own special, individual liberty as a matter of her own interest.

Further her needs were comparatively small as to governmental machinery, and taxation must be small in proportion; and she did not wish to be taxed to support a general government.

So when the call was made for each state to hold a convention to elect delegates to a Constitutional Convention, Rhode Island paid not the slightest attention to it. All the other states sent delegates, but Rhode Island sent none; and the work of that convention, grand and glorious as it was, was not shared by her.

The same party that favored inflation, or paper money, opposed the Constitution; and that party was in the majority and in power.

The General Assembly had been elected with this very thing in view. Meanwhile the loyal party, which was found mostly in the cities and commercial centers, did all in its power to induce the General Assembly to call a convention; but that body persistently refused.

Once it suggested a vote of the people in their own precincts; but that method was a failure. As state after state came into the Union, the Union party, by bonfire, parade, and loud demonstration, celebrated the event.

The country party was in power, and we have seen that elsewhere as well as in Rhode Island, it was the rural population that hated change. The action of the other states had been closely watched and their objections noted.

One thing strikes a Rhode Islander very peculiarly in regard to the adoption of the federal constitution. The people were not to vote directly upon it, but only second-hand through delegates to a state convention.

No amendment to our state constitution, even at this day, can be adopted without a majority of three-fifths of all the votes cast, the voting being directly on the proposition, and a hundred years ago no state was more democratic in its notions than Rhode Island.

Although the Philadelphia Convention had provided that the federal constitution should be ratified in the different states by conventions of delegates elected by the people for that purpose, upon the call of the General Assembly, yet this did not accord with the Rhode Island idea.

So in February, 1788, the General Assembly voted to submit the question whether the constitution of the United States should be adopted, to the voice of the people to be expressed at the polls on the fourth Monday in March.

The federalists fearing they would be out-voted, largely abstained from voting, so the vote stood two hundred and thirty-seven for the constitution, and two thousand seven hundred and eight against it, there being about four thousand voters in the state at that time.

Governor Collins, in a letter to the president of Congress written a few days after the vote was taken, gives the feeling then existing in Rhode Island, in this wise: — ‘Although this state has been singular from her sister states in the mode of collecting the sentiments of the people upon the constitution, it was not done with the least design to give any offence to the respectable body who composed the convention, or a disregard to the recommendation of Congress, but upon pure republican principles, founded upon that basis of all governments originally derived from the body of the people at large. And although, sir, the majority has been so great against adopting the Constitution, yet the people, in general, conceive that it may contain some necessary articles which could well be added and adapted to the present confederation. They are sensible that the present powers invested with Congress are incompetent for the great national government of the Union, and would heartily acquiesce in granting sufficient authority to that body to make, exercise and enforce laws throughout the states, which would tend to regulate commerce and impose duties and excise, whereby Congress might establish funds for discharging the public debt.’

A majority of the voters of the country was undoubtedly against the constitution, but convention after convention was carried by the superior address and management of its friends.

Rhode Island lacked great men, who favored the constitution, to lead her.

The requisite number of states having ratified the constitution, a government was formed under it April 30, 1789.

Our General Assembly, at its September session in that year, sent a long letter to Congress explanatory of the situation in Rhode Island, and its importance warrants my quoting a part of it.

‘The people of this state from its first settlement,’ ran the letter, ‘have been accustomed and strongly attached to a democratical form of government. They have viewed in the new constitution an approach, though perhaps but small, toward that form of government from which we have lately dissolved our connection at so much hazard and expense of life and treasure, — they have seen with pleasure the administration thereof from the most important trusts downward, committed to men who have highly merited and in whom the people of the United States place unbounded confidence. Yet, even on this circumstance, in itself so fortunate, they have apprehended danger by way of precedent. Can it be thought strange, then, that with these impressions, they should wait to see the proposed system organized and in operation, to see what further checks and securities would be agreed to and established by way of amendments, before they would adopt it as a constitution of government for themselves and their posterity?’

Rhode Island never supposed she could stand alone. In the words of her General Assembly in the letter just referred to: — ‘They know themselves to be a handful, comparatively viewed.’

This letter, as well as a former one I have quoted from, showed that she, like New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, and North Carolina, hoped to see the constitution amended.

Like the latter state she believed in getting the amendments before ratification, and so strong was the pressure for amendments that at the very first session of Congress a series of amendments was introduced and passed for ratification by the states, and Rhode Island, though the last to adopt the constitution, was the ninth state to ratify the first ten amendments to that instrument now in force; ratifying both constitution and amendments at practically the same time.

One can hardly wonder at the pressure for amendments to the original constitution when the amendments have to be resorted to for provisions that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free use thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances; that excessive bail should not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted; for right of trial by jury in civil cases; and for other highly important provisions.

The convention which finally accepted for Rhode Island and ratified the federal constitution met at South Kingston, in March, 1790, then adjourned to meet at Newport in May, and there completed its work.

=====

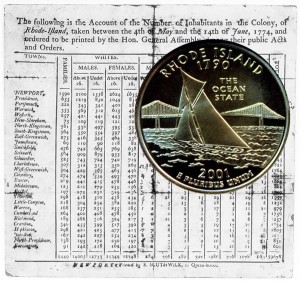

The Rhode Island State Quarter Coin shows against a population count of the area, circa 1774.